Of 1990s Taiwan—a nation transitioning from 38 years of martial law to an inchoate democracy—Edward Yang told the New Left Review, “the situation looks democratic on the outside, but you soon find that one can hide a lot of things under democracy.” Reform meant Jimmy Carter–endorsed urbanization; the sudden construction of skyscrapers across Taipei signaled the arrival of a flood of speculative foreign capital. These concrete towers sought to manifest an upward trajectory for the nation, hoping to turn the sight of its citizens toward the skies and away from their downtrodden condition. Produced in 1991, four years after the official end of Taiwan’s martial law, Tsai Ming-liang’s debut feature, Rebels of the Neon God, eddies through the reformed streets of Taipei, registering the ennui of a people caught in the shadows of a new cultural regime.

Just about everything in Tsai’s filmography can be traced back to this directorial debut: The appearance of Lee Kang-sheng, his ever-present muse. His patient camera. His obsession with un-encounters. Tsai’s early poetry of urban gloom marks a rupture in modern cinema, a chasm onto a new mythos of moviemaking concerned with delicately disclosing the meaning behind the cyclical rituals people adopt in an age when their dreams are commodified and their character conferred the status of cipher.

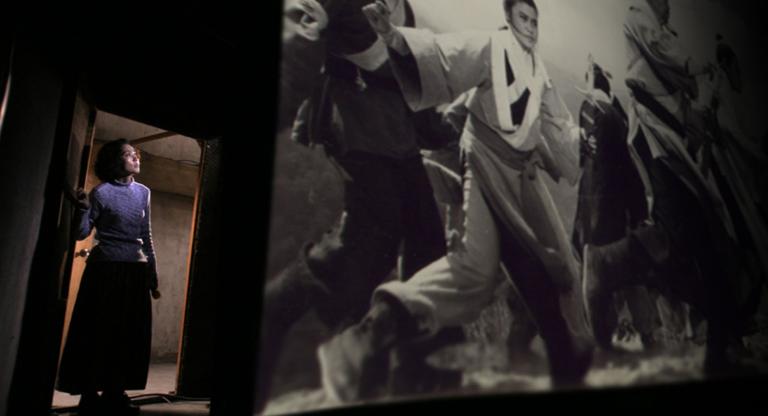

Rebels of the Neon God follows Hsiao-kang (Lee Kang-sheng), a disaffected student whose mother believes him to be the reincarnation of the tumultuous Nezha (aka “The Neon God”), girl of his dreams Ah Kuei (Yu-Wen Wang), and the petty thief Kuei is seeing, Ah Tze (Chen Chao-jung). In tracing these teenagers drunkenly roaming through Taipei, rollerblading, and button-mashing at arcades, Tsai identifies performances of defiance masking a thirst for meaning.

They’re forced to generate their own meaning while they mosey on motorbikes, and it’s both exciting and disheartening to witness their aimlessness. The rebels of the Neon God are transient travelers going nowhere, pitted against the pressure of success in service of an expanding global economy.With their parents’ hopes and prophecies in the rearview mirror, their directionless bearing disrupts the changing nation’s aspirations of development and progress. A final pan—moving from ground level up a skyscraper’s spine and landing on an overcast sky reveals Tsai’s truth: the modern city of lights will always remain shrouded in fog.

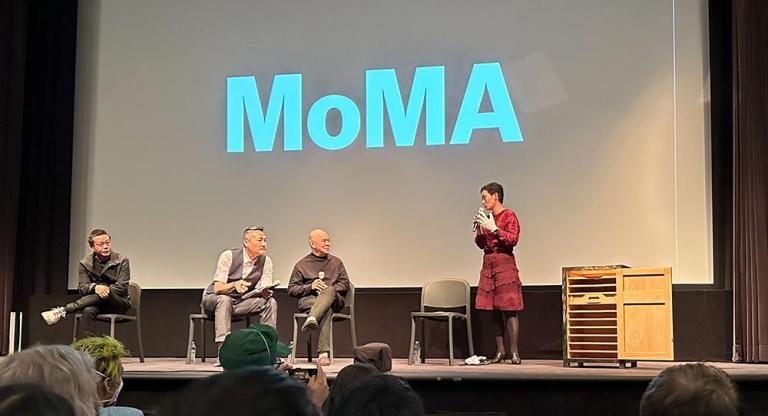

Rebels of the Neon God screens this evening, November 11, at the Museum of Modern Art as part of the series “Tsai Ming-Liang: In Dialogue with Time, Memory, and Self.” The film will also screen November 12 and 15 at Film Forum as part of the series “New Waves: Rediscovering Taiwanese Cinema of the 1980s.”