Bruce and Norman Yonemoto are, quite simply, among the most important figures in the nearly sixty-year history of artists working with video. With a body of work comprising feature films, single-channel videos, video installations, photography, and sculpture, the two brothers collaborated over the course of decades with many of the most fascinating figures in the realms of performance art, punk, porn, and Hollywood—from Patricia Arquette and Susan Tyrrell to figures as varied and storied as Mike Kelley, Mayo Thompson, Fred Halsted, Spalding Gray, and Ron Vawter. Since Norman’s death in 2014, Bruce has continued as a solo artist, producing work with Karen Finley and working in video installation. In anticipation of a Yonemoto retrospective co-presented with Electronic Arts Intermix at Anthology Film Archives, I spoke with Bruce about working with his brother and their many collaborators, producing one of Divine’s first live shows, laying the ground for Michael Lerner’s Barton Fink Oscar nod, and much more.

Karl McCool: One thing that struck me was that, before you and Norman collaborated together for the first time on Garage Sale [1976], you each had made your own documentaries. You had made Homecoming [1975], about Goldie Glitters of the Cockettes, and Norman had made a documentary about the protests and police violence at Berkeley’s People’s Park [Second Campaign, 1969].

Bruce Yonemoto: That’s right. I was going to school [at Berkeley] at the time. I told him that this was happening. So he came up with Nick, who was his partner.

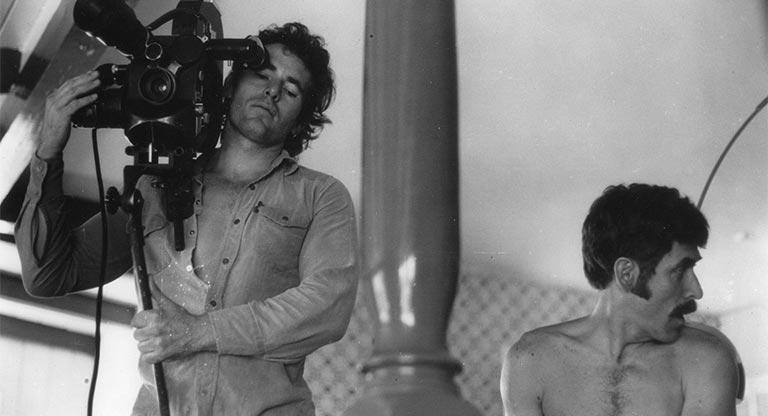

KM: Nikolai Ursin, who would go on to be the cameraperson on films and videos you made with Norman.

BY: Nick was a cinematographer, a very talented guy. He shot most of our work together. He was Norman’s partner for a long time, but then they split up. But they still saw each other every day. They had dinner every day, you know, like a marriage really. And so, yeah, he passed away from AIDS. So that was really sad.

KM: When was that?

BY: That must have been after he shot Made in Hollywood [1990], in the ’90s I guess. It was right around the cocktail thing [the discovery that combining multiple antiretroviral medicines effectively reduced HIV levels], you know what I mean?

Yeah, I think that was ’95 or ’96?

BY: So right before that, yeah.

KM: He started out by making a documentary of his own too. It was kind of astounding to realize he made a documentary about an African American trans woman in 1967 [Behind Every Good Man].

BY: Yeah, because he was at UCLA. That’s where he and Norman met. You know, UCLA at that time was really on fire, ’cause it was right after that class with Coppola and everybody. It was very active. It’s really . . . become sort of a backwater now.

KM: But you, Norman, and Nick would all move away from documentary and start working together.

BY: I studied with Germano Celant at Otis and so I started to analyze what dictated our behavior or influenced our behavior. I decided to focus on the problem drama or the soap opera, and so I started to make those, but I wanted them to look like real soap operas, real TV—you know, Hollywood-type things. And so I asked Norman and Nick to work with me for the first one, Based on Romance [1979]. I did it by myself, mostly. I think Nick still shot it, but I directed and wrote it. But after that, Norman and I collaborated more.

KM: But you all had already collaborated on Garage Sale.

BY: We collaborated on that after I came back from Japan in ’74 or ’75. That’s when I met Goldie [Glitters] in Venice at this café everyone went to, the Lafayette Café, on the boardwalk. We became friends and so, when she ran for homecoming queen, I decided to make that documentary [Homecoming], with a Portapak.

KM: Had you and Norman and Nick ever talked about how you all started separately making documentaries but then you went in this totally different direction together?

BY: Well, I’m coming from an art background, but Norman definitely is coming from a Hollywood narrative film background. That’s what he wanted to do. He wanted to make features.

KM: So what brought about the initial collaboration on Garage Sale?

BY: Well, I had made Homecoming. But even when I was at Berkeley during the late ’60s, I would go to the Palace Theater in San Francisco to see the Cockettes. We would drop acid and stay up all night and watch them, because they would just sort of riff, right? They were very messy, as opposed to the drag troupes in New York. And also, it was when Pink Flamingos [1972] and stuff like that was taking off, and there were the midnight screenings, which were fun. So we thought, Well, why not do something for the midnight screenings?

So I proposed to Norman that we do this feature, and so our parents gave us the money to do it—not very much, but yeah, they gave us the money to do it. They were really into drag too. Their favorite club in San Francisco was Finocchio’s. It was an amazing drag venue and very high end. So they would go there and take all their Japanese-American friends that came in from Chicago or someplace. And I would always just wonder, what did they think about that? You know, like, “My parents are so freaky.” But that’s why Norman and I were the way we were.

KM: Did your parents see Garage Sale?

BY: Yeah, they came to the premiere at the Fox Venice, with the Goldie Glitters look-alike contest and parade.

KM: The first ten minutes alone feature, not just drag queens, but hardcore sex and adult baby roleplay.

BY: That was Larry Coulter. He was a painter. But that was his fetish. He had all these baby costumes and he would dress these hot guys in the baby costumes and fuck or get fucked, you know.

KM: But your parents were not scandalized by the film.

BY: No, not at all. They weren't scandalized at all. I think they liked it a lot. Yeah. Funny people.

KM: And the Goldie Glitters look-alike contest was part of making this a midnight movie experience?

BY: Yeah, you know with convertibles coming to the theater, sort of like a red carpet type thing. [laughs] I mean, all these people were around. Norman and Nick lived in this little cottage up a hill in Ocean Park, in Santa Monica. There were a number of little cottages. They lived in one and Steve McGrew [who appears in Garage Sale] had one and Divine would stay there. So I got to know Divine and produced one of Divine’s first live shows. I think it was called LA Threeway? It was in a small gallery sort of towards downtown. It was really very underground. But Divine hadn’t really performed live much before. So he said yes, but when the time came around, he was freaking out and didn’t want to do it. I mean, I was really young but, you know, the show had to go on. So I just said, “Stick a steak between your legs and waddle around.” So he did that and a few other things from the films . . . But the thing about Divine was he was just this sort of heavy-set guy and then he transformed into Divine, which was really incredible.

KM: Because of the change in how he looked or how he acted?

BY: How he acted. Just an incredible personality, you know. I mean, Goldie is always just the same, you know. Like in the film, that’s Goldie.

KM: Robert Opel, probably best known for streaking at the 1974 Oscars, appears in Garage Sale alongside his characters Mr. Penis and Virginia Vagina.

BY: Well, Bob, you know, besides being a drug addict, I mean, he was great. He was such a fascinating man. You know, I really go after these people, because I am fascinated by them. So I’m like a fan. I look at myself as a fan. So I really search these people out, like Mike Kelley, or whoever. I will go to great lengths to make a contact and try to get to know them. So Bob was one of those people. He was with the LA Free Press at the time. And publishing Finger magazine—have you seen that?

KM: I have. It’s quite shocking.

BY: Yeah, fascinating guy. You know, amazing.

KM: A lengthy segment toward the end of Garage Sale II is given over to a “pissed off” Fred Halsted talking about how the LA Police Department is preventing him from showing his film LA Plays Itself [1972] uncut in LA because of the BDSM and fisting scenes. But then, on the video, which must have been shown in LA, you and Norman show clips of those very scenes from LA Plays Itself over and over. Was that meant as a kind of punk, “fuck you” gesture?

BY: Yeah, I think so. I mean, he was able to show his films elsewhere. LA Plays Itself is part of the Museum of Modern Art’s collection. You know, he was fêted, Fred Halsted, around the world. And LA . . . It was very conservative. Republican. People forget California was all Republican. Until I was old. It was depressing. San Francisco or the Bay Area would vote for Democrats and then, of course, they would never get in because it was always Republicans, like in LA, that would win.

Norman knew Fred and Joey Yale, his boyfriend, the fistee or whatever. So Norman did the interview. I think it’s fantastic. I mean, Fred is a crazy person, you know? I mean, who talks like that?

KM: Why did you call this short video Garage Sale II? It is not, strictly speaking, a sequel to the feature film.

BY: Well, because it was just following that line of X-rated irreverence. And also it was four years after Garage Sale. We would do these political works every four years around the election.

KM: It struck me, looking back at the work you and Norman did from the ’70s through the ’90s, there are different approaches to “Asianness” and “Americanness.” There are the works, like Green Card [1982] or Japan in Paris in LA [1996], which tell the stories of Japanese or Japanese-American people. But then there are works like Based on Romance, where you have a white American couple but they’re on tatami and their story is shot like an Ozu film, at tatami level. Or, you know, you have Godzilla attacking Goldie Glitters.

BY: It’s an interesting question. I think it has to go back to more of my biography, in a way, because I’ve always identified with being Asian, whereas Norman did not. I mean, he thought he was blond, I think, until he was a teenager or something. As a child, he loved Flash Gordon, the TV show. So he would wanna play Flash Gordon, you know? And the only other main character, of course, was Ming the Merciless. And so I would play Ming the Merciless and he would play Flash Gordon. But, of course, I was fine with that because I liked Ming the Merciless. I thought he was great ’cause he controlled fire and had all these powers, you know?

He really didn’t have much interest in going to Japan. I don’t think he ever had an Asian boyfriend. And my other brothers weren’t interested either, which was sort of weird to me. I know my mother, before the war, would go to Japan every year and visit relatives there. She spoke Japanese very well, taught it at the Buddhist temple in Sacramento, stuff like that. And my father . . . his Japanese wasn’t so great. . . . But he was in a white community. Basically, all his friends were white. His best friend was named Norman. And that’s why Norman had that name. Probably I took more after my mother and the rest of my brothers took after my father in a way.

KM: And that extended to the videos you and Norman made?

BY: Yeah. Green Card is based on this relationship I had. Based on Romance . . . I guess just because the art world was so white I just put them in this Japanese environment. One of my professors, Shiro Ikegawa, had those rooms in his house. I remember he had a sushi bar in his house that Allan Kaprow and people like that would go to. He would have these sushi chefs come in.

KM: You got married to the star of Green Card, Sumie Nobuhara, who in fact needed a green card, at the video’s premiere.

BY: Well, we were a couple when we were in school. But this was after we had gotten out of our MFA program, so by then we weren’t together. So it really was a green card marriage. And the whole script I wrote was based on our relationship.

KM: You met Sumie at Otis, along with Jeffrey Vallance, with whom you and Norman would collaborate on your video Blinky [1988]. Ulysses Jenkins was also there at that time. It occurred to me that both you and Ulysses would have entered the MFA program at Otis already having made important film and video work.

BY: We studied with the same professors. Charlie White was there. You know, that’s the reason I went to Otis instead of CalArts. Because not only was it cheaper and closer to where I lived, it was all more multicultural and, you know, there were minority students, whereas CalArts was all white. So we knew each other. [Jenkins] went in that direction of community activity and public access, while I was more interested in this narrative deconstruction, Pictures Generation–type thing.

KM: Later you and Patti Podesta founded the video program at LACE.

BY: Patti was a very close friend of mine. I think that LACE was a nexus for many of the artists that I knew, such as Tony Oursler, Jim Shaw, Mike Kelley. And so Patti and I started the video program together. Because there was no program like that in Los Angeles. There was Long Beach [Museum of Art]. We would edit our work there.

KM: During this same period, Norman wrote the screenplays for the feature films Chatterbox! [1977] and Savage Streets [1984]. But his time in the film industry left him disillusioned. He and Nick also made a number of gay porn films [under the pseudonyms Jason Sato and Nick Elliot, respectively].

BY: Well, that’s the way he supported himself.

KM: Through the porn films.

BY: Through the porn films, yeah. And then the videos after that. He was really into porn and the whole gay scene. The Circus of Books. There was a whole scene around John Schlesinger, all these gay men that were part of Hollywood. He would go to those parties. I remember him telling me some stories. They would stage these sex parties where he was a captured Vietnamese soldier or something. He was playing that role at some rich person’s house, things like that.

KM: Was this before he made his “anti–Vietnam War porno” Brothers [1973]?

BY: Probably around the same time. It was the only anti-war gay porno. Of course, who else is gonna make that?

KM: Why did he stop making porn films?

BY: Well, I think it sort of ran its course in a way, after VHS. Although Norman was one of the first people to make porn on video for video [Big Men on Campus: The Fraternity, 1978]. But after a while, there were no more real features, you know?

KM: Is it true that the producer character played by Michael Lerner in Made in Hollywood was based on [the producer] Samuel Z. Arkoff?

BY: To a certain extent, yeah. ’Cause Norman hated him. He wrote Chatterbox! for him and Savage Streets. Norman couldn’t compromise and he just thought he knew everything. You know, it’s a very clichéd Jewish producer role, which Michael Lerner did perfectly. And actually, Michael Lerner, you know, he developed that character for Made in Hollywood, but then he went on to do the same character in Barton Fink [1991], and he got a nomination for that. So he owes us, but whatever.

KM: One of the fascinating aspects of Made in Hollywood is that you have these movie actors like Patricia Arquette and Michael Lerner performing alongside experimental theater actors like Ron Vawter and Greg Mehrten and performance artists like Tim Miller, Michael Smith, and Rachel Rosenthal.

BY: Rachel, of course, I knew her background, this Parisian, Jewish, rich family. And so I knew she could pull that off. Mike Smith’s a little stiff, but that’s ok, you know, he always is. Of course I had seen Ron in the Wooster Group and thought he was great. . . .

The Tammy character [played by Patricia Arquette] is based on that Tammy series, which starred Debbie Reynolds and then Sandra Dee. So Sandra Dee in Tammy Tell Me True [1961] goes to college And she’s still dressed in all this gingham and stuff like that, because she’s from the bayous or whatever. And she proceeds to tell every professor on campus how to be happy. So she tells the art professor, “You can’t paint abstraction because you’re never gonna be happy.” So we have Tammy coming to Hollywood. So we wanted that type of Hollywood actor for this Hollywood character.

KM: And you and Norman collaborated with Mary Woronov on many projects.

BY: Well, I guess it started when I was getting my MFA, because that’s when I first met her, in the late ’70s. That’s when I would go with her to punk clubs. She’s a horrible person. It’s true. But I love her. She’s very mean, you know. She can be very mean.

KM: That was often her persona, in the Warhol films and later, in a lot of the exploitation films.

BY: But she’s not mean in the Paul Bartel films.

KM: That’s true.

BY: In fact, I didn’t like that Mary in the Paul Bartel films. I didn’t think it was really who Mary was. I think one of her best roles is in Made in Hollywood, to tell the truth. I think she’s great. And also in Kappa [1986]. She’s fantastic in Kappa too.

KM: What was it like working with Susan Tyrrell on Japan in Paris in LA?

BY: Susan was a trip. Major alcoholic. On set she was always carrying a Big Gulp filled with vodka. . . . The Japanese actor [Yusuke Todo] wasn’t so experienced, so she was very nurturing and supportive.

KM: In the late ’90s you started to produce work as a solo artist, after collaborating for decades with your brother. You started doing solo work after Norman had his first stroke?

BY: Well, I guess I had already started with the installations. Framed [1989] was really a collaboration. But you know thinking about the installation, sculpturally, is definitely not Norman. He was so focused on film.

KM: And did it feel different once you started to produce single-channel work as Bruce Yonemoto?

BY: Well, to be perfectly honest, I cannot make a feature. And I don’t pretend that I can. Nor do I particularly want to, because it’s a specific language and you have to really be dedicated to it. Even for Norman, it took him so long to master that.

KM: What had been the division of labor between you and Norman? It sounds like Norman was the editor.

BY: Yes, Norman did the editing. I think that was his strength, really, his genius. He was fantastic. I would come up with a lot of the script. But he hated my writing, the way I organized things, and so he would organize the dialogue or whatever I wrote. I would cast, work on locations, find the cheapest place to edit, things like that. But he would go over this material over and over again while he was in bed. The only thing that got him out of bed was sex. So he would just stay in bed and watch the videos and think about them over and over again. The Z Channel, there was the Z Channel. He would just watch TV in bed, you know?

KM: You have a new work showing at Anthology?

BY: I’ve been working on a new piece with Eder Santos called Cosmopolitan [2022]. I shot it three years ago in Mexico City. I always thought that Eder could edit it. I thought this might make an interesting video in his style—which a lot of people don’t like, to tell you the truth. But you should see it.

“Bruce & Norman Yonemoto” runs March 17–24 at Anthology Film Archives.