If you come across any mention of Fred Halsted, typically one of the first things you will read is that Halsted is the only gay porn filmmaker to have his porn films in the collection of MoMA. During the home video era, box art for the (bowdlerized, censored) VHS release of his seminal 1972 film LA Plays Itself would read, “Part of the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art,” certainly advertising copy no other porn tape could boast. It is fitting then – if also wonderfully unexpected – that on January 30 and February 1 MoMA will screen new 4K preservations of all three Halsted films in its collection – his 1972 “trisexual” short Sex Garage (featuring hardcore heterosexual and homosexual sex, as well as sex between a biker and the exhaust pipe of his motorcycle), the aforementioned LA Plays Itself (widely considered his masterwork and the film that introduced fisting to porn audiences), and his 1975 followup Sextool. Shot on 35mm (unheard of for gay porn) and alternating rough BDSM scenes with scenes of trans women and drag queens at a chic party, Sextool finds Halsted again rethinking the possibilities of the gay porn film. A box office failure, never given general release on home video and long locked away in the MoMA archive, this new 4K preservation provides a rare opportunity to see one of the most ambitious and remarkable films in the genre.

These new preservations (along with the original 16mm trailer for Sextool) screen as part of “Now We Think as We Fuck”: Queer Liberation to Activism , a marvelously wide-ranging screening series organized by Carson Parish, reflecting the breadth of queer film and video holdings at the museum, from Halsted to Avery Willard, Andy Warhol, Barbara Hammer, Cheryl Dunye, and Marlon Riggs (who gives the series its powerful title). These Halsted screenings might be seen not only as a vital addition to “Now We Think as We Fuck” but also as an extension of another very welcome MoMA screening series, from a couple months back, Re-Viewing Cineprobe,1968–2002 , organized by Sophie Cavoulacos. It was for the (in this case, all too aptly named) Cineprobe series that curators Adrienne Mancia and Laurence Kardish invited Halsted to present his work at MoMA, placing his hardcore films in the context of a program known for screening avant-garde filmmakers such as Stan Brakhage, Hollis Frampton, or Michael Snow. The Cineprobe event was a landmark achievement for Halsted — the capacity audience reportedly included Groucho Marx. (Try to picture that when watching LA Plays Itself.) However, the evening was not without its detractors. Protestors outside MoMA handed out leaflets describing LA Plays Itself as “an exploitation film, made by a self-described petty criminal and hustler” and excoriating the museum for applying “the pretentious label of ‘Art’” to “expressions of anti-homosexuality.”

Halsted had already earned much notoriety by this point. Two years before his 1974 appearance at MoMA, his debut feature LA Plays Itself had already made an enormous impact, perhaps only rivaled by Wakefield Poole’s Boys in the Sand, in making gay porn (and porn more generally) worthy of serious consideration as cinema and, along with Deep Throat (released months after Poole’s and Halsted’s films), ushering in the period of “porno chic.” Indeed, in his “Movie Journal” column for the Village Voice, Jonas Mekas would wonder if LA Plays Itself represented “the beginning of a movement of porno cinema as art.” Sadly, in retrospect, the period between the 1972 release of LA Plays Itself and the 1974 Cineprobe screening represents an exceedingly brief moment in cinema history, perhaps the only time in which a self-taught filmmaker, with no industry ties or gallery representation, who never held a regular job and never even had a social security number, could present such revolutionary work at venues like MoMA.

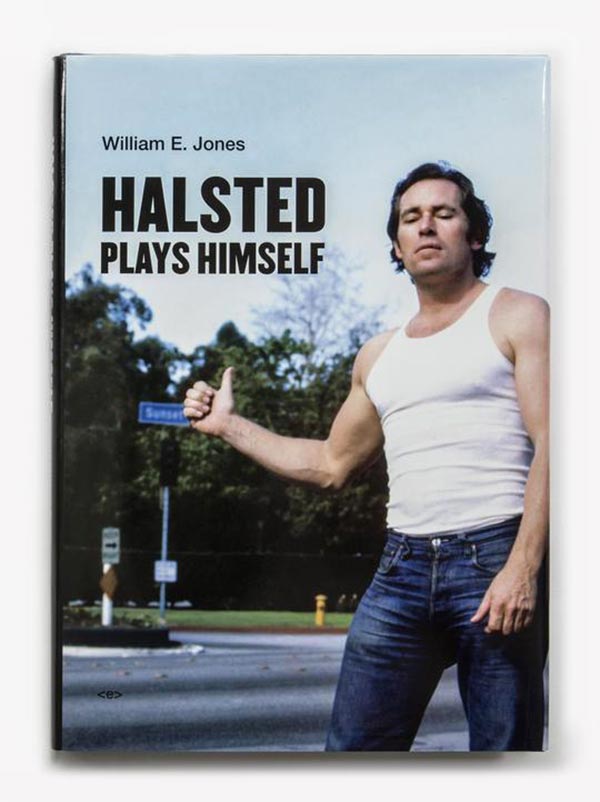

Thankfully, the January 30 Halsted screenings will feature discussions with artist, film- and videomaker, and writer William E. Jones, alongside Lauren Halsted, niece to the groundbreaking filmmaker, who died in 1989. Jones literally wrote the book on Halsted – Halsted Plays Himself, an indispensable resource first published in 2010, when there was not even a Wikipedia entry for Halsted (although Patrick Moore had devoted an affecting chapter to Halsted in his invaluable 2004 book Beyond Shame: Reclaiming the Abandoned History of Radical Gay Sexuality). A new edition of Halsted Plays Himself, with a new afterward by Jones, is forthcoming. Jones is currently at work on his second novel. Halsted appears as a character in his first novel, I’m Open to Anything, which was published in 2019.

On the occasion of these screenings and his appearance at MoMA with Lauren Halsted, I interviewed Jones. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

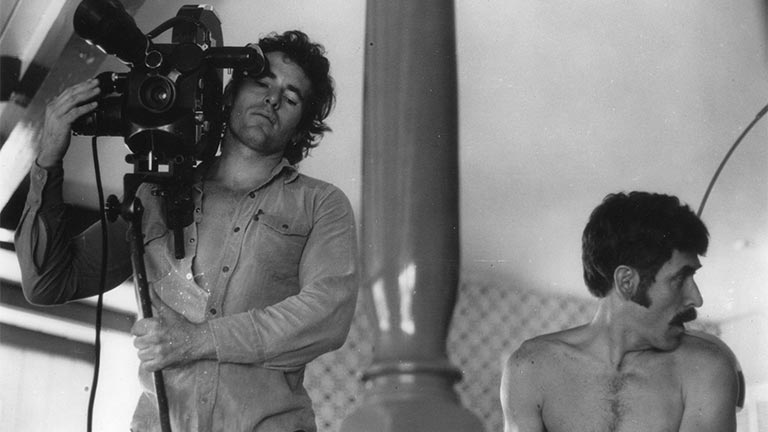

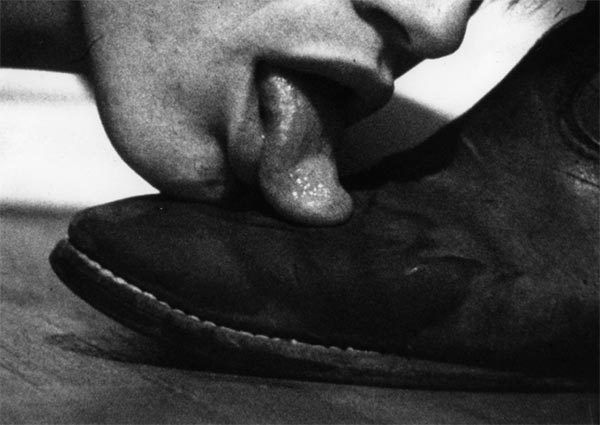

LA Plays Itself. Courtesy MoMA Film Archives.

Looking forward to the screening of these new 4K preservations and thinking back to his 1974 Cineprobe evening, I wonder if you could talk a bit about the role MoMA played in Halsted’s career?

MoMA did a great thing by including Fred in their programming and archive, but very little developed for Fred as a result of it. He didn’t have what people today would call a career in art or film. It is possible that the Cineprobe screening gave him the confidence to complete Sextool in 35mm, but this ended in disaster. Almost no porn theaters could project 35mm, and by 1975, “porno chic” had run its course, and legitimate theaters weren’t interested anymore. Fred’s short-lived prestige proved to be an historical anomaly, though few realized it at the time. As far as the commercial prospects of a gay porn film with the imprimatur of MoMA are concerned, I’d say they have been minimal. It’s important to keep in mind that the gay industry brings in a fraction of the revenue that straight porn does, and that most consumers simply want the latest product and have little interest in aesthetics or history. The fans of Fred’s early art films are a subculture within a subculture. I don’t mean to dismiss the importance of this, but realistically speaking, it wasn’t enough to provide Fred with a livelihood. He had to become a conventional gay porn director and producer to pay the bills.

Why do you think Halsted caught the attention of Mancia and Kardish at MoMA and not gay porn auteurs with ties to the New York art world and culture industry, such as Wakefield Poole, Arch Brown, or Jack Deveau?

Fred Halsted was the only person you mention who was both a director and a performer in porn. He exuded a personal charisma that was hard to resist. Since Fred didn’t live in New York, it’s likely the curators had fewer preconceived ideas about him. He was free to be just a crazy (and very attractive) guy from Los Angeles. To me, it’s a shame that there was only room for one, but I’m thankful they chose Fred, because he’s my favorite of the bunch.

The Cineprobe screening was controversial, not only because MoMA still received NEA money at that time – causing Mancia and Kardish to take some heat from the trustees – but also because of the reaction it received from some self-appointed representatives of the nascent gay community, who protested outside the museum.

Fred was capable of saying anything. This made him a great interview subject (and interesting as the subject of a biography), but terrible at politics. Representative members of a community must say things that are predictable and in keeping with a party line. Fred was an individualist to the end with no patience for the work of collective politics. There is a certain pathos in that, but at least he was honest with himself. He didn’t feel part of any community. He was a pioneer, and he saw the gay rights movement, in its conformism (and later, conservatism), leave him behind. I respect his idiosyncrasies, even though they prevented him from addressing a wider gay audience.

Boyd McDonald drew a useful distinction between the word “homosexual,” describing men who have sex with men, and the word “gay,” describing those who make public declarations about their sexuality, but who are often forced into a kind of hypocrisy, presenting a respectable asexual image to the world for the sake of political legitimacy. In this formulation, Fred was entirely on the side of the homosexual.

Regarding that specific protest, the group outside MoMA objected to how Fred represented fist fucking, maintaining that anyone who saw LA Plays Itself and tried to have sex that way at home would injure his partner. This is a valid point, but Fred never intended to make an instructional film about fisting.

Sex Garage. Courtesy MoMA Film Archives.

Part of what makes Halsted and his films so fascinating is they could have only happened in this brief window between the rise of hardcore as an outlaw form and the professionalization of the porn industry. Halsted was an untrained filmmaker – an autodidact, a working class, politically incorrect, sui generis figure. There is perhaps a similar fascination to Boyd McDonald, whom you also wrote a book about.

You’ve summed up quite precisely why I was attracted to Fred Halsted as a subject. His success was the result of very special historical circumstances that proved to be fleeting. He is a reminder of how things could have turned out, and perhaps he gives us an indication of how things could be better in the future. Both Halsted and McDonald lacked any sense of propriety in their work. It’s not an easy way to live.

High on my list of tragically unrealized film projects must be the proposed collaboration between Halsted and William S. Burroughs on a film adaptation of The Wild Boys. I wonder if the failure of this project shows us the limits of what was possible, even at this time, even for a figure like Halsted?

It wasn’t possible then, and it’s even less possible now. I have nothing but contempt for the neo-Victorian moment in which we find ourselves, and my immediate response is to offer support to obscenity – not the real obscenity of ethnic cleansing with high tech weapons or wholesale environmental destruction – but the legalistic variety, that is, images and descriptions of people fucking.

You write of Halsted that his “films have many fans but few advocates.” Peter Berlin just released a lavish photography book, a few years ago Tom of Finland (Touko Valio Laaksonen) had a posthumous exhibition at Artists Space here in New York and his erotic drawings, like those of Mike Kuchar, now have gallery representation and fetch high prices. I wonder if you share my suspicion that, were he still with us, Halsted would not receive this attention?

Peter Berlin, Tom of Finland, and Mike Kuchar make (or made) objects that have a presence in the art world, but their work goes against the grain of a market increasingly devoted to rewarding high-end brand names. Of course, this could change at any moment, and the scene seems ripe for it. I detect a vast quantum of boredom at the art events I attend.

Fred Halsted’s position in all this is tenuous, because he was a filmmaker. A filmmaker’s works have duration, and in this age of instantaneous gratification, they’re a hard sell. Even Andy Warhol, the branded artist par excellence, is ill served in this environment. His recent retrospective included only a few of his films, which I consider to be the very greatest artistic works he made. To appreciate a film fully, one must give oneself over to it in a way that’s completely out of sync with current cultural priorities.

Some years after writing Halsted Plays Himself, you have just returned to Halsted, making him a minor but pivotal character in your new novel I’m Open to Anything.

Due to production costs, Semiotext(e) placed a limit on the number of pages they would have printed for Halsted Plays Himself, so I could only include one long article in the book. I chose an interview with Mikhail Itkin for several reasons: both Fred and his partner Joey Yale participated in it; as an activist, Itkin could challenge Fred’s more controversial assertions about gay politics; finally, the piece came out as a two-part feature in a short-lived publication called Entertainment West, and there was a mistake in its layout. I saw a chance to “rescue” an article that was not only all but impossible to find but also hard to read. In making this choice, I excluded the interviews that appeared in the PhD dissertation about the early gay porn industry by Paul Alcuin Siebenand, who was a Catholic priest. (One reviewer of the book mentioned this omission, and I admit it was a tough choice.) Siebenand’s dissertation is available on microfilm from UMI, and a pdf can be downloaded from the internet. I met Father Paul, and he not only gave me his personal copy of the dissertation (bound in pink), but he allowed me to use the text however I wished. I decided to adapt Fred’s words as dialogue for the scene where the narrator meets him in I’m Open to Anything. The interview is now in print for anyone to read, in an edited, fictionalized form. Halsted Plays Himself was published almost ten years ago, and I’m hoping the novel (among other things) informs a new audience about Fred.

You will introduce both sets of screenings on the 30th with Lauren Halsted, Fred Halsted’s niece.

Lauren emailed me out of the blue because she had read and appreciated my book. She would like to write her own book about Fred, and I have encouraged her. We have met for lunch a few times and discussed the uncle she didn’t have a chance to know well. Her father was Fred’s brother, and I understand this was not a happy sibling relationship. He did not consent to speak with me when I was researching my book, but Lauren is having some success in getting him to talk. Through her father, she has an intimate view of Fred in his youth. Lauren can also correct any factual errors I made because of a lack of specific testimony. I’ll deal with these in the afterword of the second printing of Halsted Plays Himself, which should come out next year.

Header image courtesy Curtis Taylor and MoMA Film Archives.