Critiques of the racism in the film industry often pass over the camera itself as a complicit agent. Never neutral, visual technologies are clearly marked and shaped by ideological forces. Photography developed over the course of the nineteenth century, meaning the camera emerged during one of the peaks of Western colonialism and imperialism. Not only did photographic technologies coincide with these projects of domination, they facilitated the categorization and regulation of oppressed populations. Photography solidified categories of racialized, lesser “Others,” functioning as an alibi for empire’s brutal paternalism. As the camera evolved and became a cinematic instrument, its material racism remained. Color cards used from the 1950s to 1990s to calibrate light and balance pigmentation used a white woman as a universal reference. Engineered to favor and accurately render a limited range of skin tones, photographic and film stock were reflective of racial hierarchies. Attention to the machinery of the camera also punctures any fantasies that a hard line can be drawn between non-Western and Western filmmaking. As Stuart Hall cautioned, absolutist divisions of “the West and the Rest” are ahistorical simplifications, ultimately functioning to stabilize discourses of the former’s neutrality and superiority.

The false premise of the objectivity of visual technologies is the starting point for Prism (2021), a collaborative documentary between Cameroonian Rosine Mbakam, Burkinabé Eléonore Yameogo, and Belgian An van. Dienderen. The film is stylistically variable, assembled from interview clips, behind the scenes footage, recorded Skype conversations, and a few more abstract and theatrical sequences. Prism was conceived as a “chain letter,” a visual relay between the filmmakers. Rejecting the more typical documentary orientation toward establishing mastery over a subject and presenting a neatly tied narrative, the film foregrounds the tentativeness and non-deterministic uncertainty of its approach. It begins with a dark screen and an off-voice: “Maybe the film can start like this. We film ourselves, in a static shot, with An in the middle, see? As if we’re taking a photo. In our subconscious we hear an off-voice, from each of us, that wonders what we will look like in this photo or image.” Prism opens in process, scrambling the temporality of production and using sound to conjure an unrealized image. Fittingly, the filmmakers start their collective questioning of image by not yielding any visual information at all.

One of the most striking recurring inserts in this prismatic documentary is a re-staging of Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s painting, Portrait de négresse (1800). Although long anonymized, it has emerged that the sitter was named Madeleine and was from Guadeloupe. A freed slave, her likeness was painted in the interim period between the abolition of slavery in French colonies in 1794 and its re-instatement in 1802. Yet the political space of formal abolition, like that of formal decolonization, did not eradicate the power structures that would make this a compelled image: consent to be represented was not available to Madeleine. While the painting itself hangs immobile in the Louvre, the image has circulated widely. Reproduced frequently as a shorthand for the fate of any black women of the period or for overlapping issues of race and gender in painting, it might also be familiar from Beyoncé and Jay-Z’s “Apeshit” (2020) music video, or from having been turned into a stamp by the French postal service in February 2020.

In Prism, the painting is dilated into an extended, animated tableau. The film attempts to rewrite the portrait, to restore the négresse to herself, creating a new set of conditions in which she can self-authorize her appearance. A black woman walks onto a set, jeans and sneakers visible beneath a white sheet arranged like a dress. She sits on a brown leather armchair draped with blue fabric and takes out a compact, beginning to apply her makeup. With this small act, the sitter is determining how she will look. Mbakam’s voiceover during this scene specifies that her aim was to make Madeleine look more confident, to cover the breast which is exposed in the painting—in a way, to protect her from the accumulation of gazes she has been subjected to over time. The sitter names herself as Madeleine and “Hottentot Venus,” historicizing her appearance in the European visual regime that, along the axes of racialized and gendered violence, served as an avenue for the containment and debasement of black women with particular virulence.

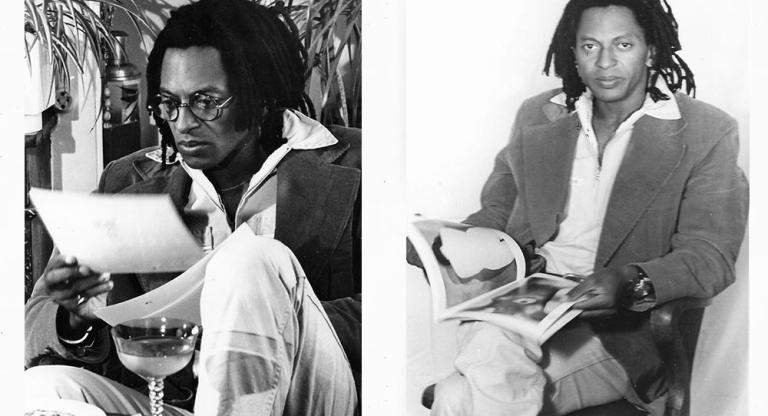

Yameogo’s section of the documentary serves to extend the more concrete and contemporary concerns operating in their shared investigation. She includes actor Tella Kpomahou and filmmakers Sylvestre Amoussou and Diarra Sourank, who speak to the micro-dimensions of how black skin has been filmed (with poor lighting and inadequate makeup), contextualized alongside Paulin Soumanou Vieyra’s groundbreaking Afrique sur Seine (1955). Mbakam makes a critical intervention towards the end of Prism, stating plainly that technological problems can be fixed and that it is possible for black skin to be beautifully lit on camera. But the problem is not only technical, as Mbakam says, the real issue is the ideological stakes hidden in the machine. The task is to stop ignoring them.

Les Prières de Delphine (Delphine's Prayers, 2021) engages in a similar set of concerns, and like Prism, begins in the unsteadiness of process. As the camera adjusts its angle, Delphine looks into the lens and asks, “We’re starting now?” with a tinge of alarm. She is reassured by the offscreen Mbakam that there will be edits and cuts. Delphine’s voice shifts to a more imperious tone: “Find yourself a chair, or I won’t be comfortable […] So I can feel relaxed and not stressed.” Within a few seconds, the directorial dynamic flips. Where Prism is more historical and expository, Les Prières de Delphine is an exercise in shifting the power structures of filmmaking. The genesis of the film itself was that Delphine demanded it be made, generating a dynamic of co-authorship between her and Mbakam. Over the course of the film, their relationship is clarified: they have been friends for years, and this intimacy is made especially evident in the final minutes, in which Delphine braids the filmmaker’s hair while Mbakam’s voiceover presents a loving testament to her.

The entirety of the film takes place in the somewhat claustrophobic cocoon of Delphine’s room in Belgium. She lounges in her bed, sometimes smoking, at other times cleaning or watching a show. In one of several monologues, Delphine covers her sister’s pregnancy, their father’s refusal to help, and her own rape and turn to sex work in a visceral, molecular exposition of what the combined legacies of colonialism and entrenched patriarchal dynamics can mean for a young woman in her position. The emotional exposure is startling and excruciating, but any potential inflections of exploitative voyeurism are tempered by the fact that, from the opening seconds, we have seen her call the shots. A later scene ends with her saying, “We’re done for today. Nobody will stop this story from being told. Not as long as I’m the pilot of this plane.”

Taken together, the two films question and turn over what forms of sovereignty can be sought from the camera and from cinema. Prism and Les Prières de Delphine suggest that there are no absolute correctives: the machine cannot be overcome, history is not erased. What is available is a set of negotiations—unsatisfactory and imperfect, but a reminder that although oppositional and counter-hegemonic cinematic practices have insurmountable limitations, they still offer at least a reckoning with covert constructions of power, and maybe even a way to challenge them.

The series Prisms and Portraits: The Films of Rosine Mbakam runs at BAM October 8 –14.