“It happened by the grace of God that Joseph Santangelo won his wife in a card game.” Embedded in this opening line of the Household Saints (1993), is the passive position of the woman, referred to by role and without a name. But soon the focus and priority of the movie, based on Francine Prose’s 1981 book, directs its attention from Joseph (Vincent D’Onofrio) to Catherine Falconetti (Tracey Ullman, with a scowl so hardened you could cut glass with it). Through her debut feature, True Love (1989)—which won the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance—and her follow-up, Dogfight (1991), filmmaker Nancy Savoca has proven herself a sensitive observer of the unidealized women, often at odds with their environment and prevailing social norms. Her third and most ambitious feature, Household Saints, follows suit while asking whether it’s possible to live a pious life in a secular world.

Set in Manhattan’s Little Italy in the 1940s, the film begins as a marriage story of the couple navigating their new, shared life, complicated by Joseph’s devoutly religious and superstitious mother (Judith Malina). Just as we settle into its narrative rhythms, and the character’s newfound prosperity, the film pivots to their teenage daughter Teresa (Lili Taylor) who becomes increasingly obsessed with God and threatens to join the convent, much to her parents’ chagrin. Locating the extraordinary in the ordinary, Savoca renders fragments of Teresa’s visions—divine and otherwise—through surreal transitions and formal flourishes of magical realism, while the serendipitously circuitous script allows everything its rightful place by the final scenes. Blending bleak comedy and heartfelt sincerity, the film is a multigenerational fable that whorls in the oppositional forces of luck and faith, fate and self-determination. The stacked cast of supporting players—Michael Imperioli, Michael Rispoli, Victor Argo—adds to the film’s neighborhood-legend quality. On the occasion of Household Saints’ restoration, I spoke with Savoca about the film, religion, and sausage.

Elissa Suh: Congrats on the restoration! How does it feel having the film come out to a new audience 30 years later?

Nancy Savoca: I was not expecting this. I thought it was going to go out on DVD. The fact that we were invited to the New York Film Festival was just wonderful—and then this response where people wanted to speak about it. Everyone we talked to, including the technicians who were doing their beautiful work, were reacting to the movie. I'm so pleasantly surprised. More than pleasant: deliriously surprised. This movie's like 30 years old, and I’m so happy that people want to talk about it because I'm so still into what this movie’s about.

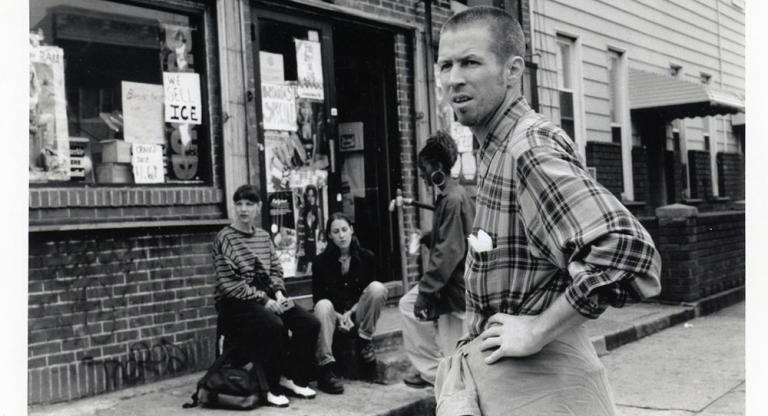

ES: I saw the movie at the NYFF where many were struck by that image of Lili Taylor and Michael Imperioli standing outside a theater playing Last Year at Marienbad. You’d worked with Lili before. How did Michael get involved with the film, and what was it like working with him?

NS: I love his character so, so, so much. I was worried about who would be able to embody him, Leonard Villanova, because on paper I felt like I knew him. I knew a Leonard. I think we all know a Leonard. There's an attraction between him and Teresa, Lili Taylor’s character. She just doesn't know where to place it so she doesn't acknowledge it. But because he's someone important to her, I didn't want him to be a stereotype that was easy to lampoon. I needed an actor who was going to pull this off and give him many dimensions, and it was one of our casting directors, Julie Madison, who said Michael Imperioli. He had done Goodfellas [1990] at that point and another small role. When we met, he was just so smart, the way he spoke to us about our movie. We thought, Oh man, he's going to do a great job.

ES: I don't know if you're aware but there is apparently renewed interest in Catholicism amongst certain young people downtown. To be clear, I don't know how seriously these people are taking their faith, and some of it is reactionary, but in any case the word is that some people are embracing Catholicism for whatever reasons.

NS: You just shocked me. So much stuff to learn! It's a younger generation, so it makes sense that I'm not aware, but I think that's really interesting. I get a feeling there are people today that are either way outside the box when it comes to religion or finding some comfort in joining something that's established, so I'm just fascinated when you say that. With any kind of deep-thinking crowd, when you're trying to figure something out, the question is do we throw the whole thing out or would we be missing something that could still be of use?

I threw the baby out with the bathwater in terms of Catholicism and my upbringing at some point in my twenties. But it always nudged me, and I think it's just a spiritual path for me now. When this story came along, it was an excuse for me to be able to delve into it. I always do research—for the characters, for the film, for my part as a director in the film—but it got deeper. Making this movie helped me define some things, so that when I think about that part of myself, it doesn't necessarily have to fall into any kind of organized thing.

ES: When you say you threw the baby out with the bathwater, was there anything specific that sparked your initial skepticisms? Maybe something you read or saw?

NS: I think it came right after my family went back to live in Argentina when I was 12. It's not anymore, but at that time it was such a Catholic country. Religion was everywhere. It was part of the fabric of life in a way that it wasn't in New York, where there were many different kinds of people around me. Then suddenly I'm in this monoculture, where everybody goes to Mass, everybody did Stations of the Cross, everybody went to Good Friday. Religion was on the streets—and it was kind of beautiful. I ended up going to Catholic school for the first time and I was just like, Wow, this is really good. I can see this life.

We were supposed to stay there forever, but we turned around about nine months later and came back to New York. I went to the library and picked up a book called The Passover Plot, which took on the Christian story in a historical way. And it blew my mind. That kind of turned me. I started thinking I could question all of this and ask about what kind of stories I’d been told here. I kind of felt like Catherine in the movie. If there is an entity greater than me out there, I don't need to bother it. I don't think it pays attention to me. I'm pretty much going to live my life—without the "please do this for me and do that for me." It's like I was Carmela and little Teresa as a child, then I moved past that stage in my life [and became Catherine].

ES: I’m not Catholic, but I grew up Protestant and experienced something similar. My parents are also immigrants with their own set of superstitions so I found myself on familiar ground watching the film.

NS: I love it. I always think back to when we did our first movie, True Love (1989). I kept hearing that it was too specific. And then the responses that people had to it made me realize that it was because we were so specific that more people could find themselves in it. This happens to me when I watch a movie; it could be another country, another culture, but the more specific it is, the more I find myself in it. And that's the paradox. I don't understand it, but there's something cool about how we can enter these worlds and find ourselves. I think it was Roger Ebert who said that films are empathy machines.

ES: When we are introduced to Catherine she is stubborn, scowling very harshly, and she can't cook, which is—

NS: —a big problem.

ES: Nine out of ten times in the movies, the food scenes will showcase an appetizing spread. But not here.

NS: Those food scenes for me were my equivalent of a horror movie. We have pasta sticking to each other, the meat is raw, the oven's not working. The greens are gritty and most of them fell on the floor when the sink overflowed. I remember those details even before the restoration. We always used to joke that if we were having a bad day in the kitchen, it was "I'm having a Catherine Day." I also come from a foodie family. My father cooked professionally in restaurants in New York, and my mom cooked for everybody, you know. That was just the worst thing that could happen to you because your job as a cook is a lot like directing. You want to give people an experience, and it should be kind of seamless, not showing any effort—even though you do make a lot of effort behind the scenes. When you present the meal and you sit down to eat, it should be about that moment—and Catherine was having a hard time with that. What a nightmare.

ES: Speaking of food, sausage is a recurring motif, and the end credits listed a sausage consultant.

NS: We should have had a bread consultant as well. We knew we were going to make close ups of the bread, but we filmed in North Carolina, not a place with a big Italian-American population, and I could not find local bread that looked like the ones from Terranova—very dark outside and light inside with lots of holes in it. We had to bring bread from New York and bring it to a bakery down there.

For sausage, Judith Malina informed us on set that she's vegetarian and will not touch her friends who have been murdered. We were like Really? Oh, shit. Again, we're doing close ups of this and need a crane shot of her kneading the meat. We had a terrific creative art department and Kalina Ivanov, the production designer, got to work on finding the real sausage, talking to the sausage consultant about how that all worked out so that they could mimic the look of the pork—all parts of it like the gristle, the fat, the casing. It was important for the movie that it looked real.

ES: Do you have any idea what you ended up using for the sausages?

NS: When we did the restoration I was in touch with Kalina so I asked if still had the recipe somewhere in her notes. She's looking, but I do remember kidney beans were definitely a part of it.

ES: You're one of the pioneering independent filmmakers of New York, and I’m curious what sort of challenges you were up against, especially as a woman. In the production notes, Tracey Ullman says you did not and will not compromise.

NS: I mostly got in trouble by not compromising. That was part of the issues that later reared their head on me. I couldn't articulate it then, but I've had time to think—not dwell—on it and just have more of an awareness of it, which I think is really good. I teach a lot, and I tell all my students—especially the students who come from [a] marginalized background—to show up as the number one thing. Show up, because it's a revolution that you're there. Lots of things will get more challenging because you're basically dealing with folks who are not used to who you are. And you can facilitate as much as you can in order to get that movie made, but in the end, try and get the movie made that you want. And that's been the focus for me.

I think my biggest challenge has always been in casting, because your observation was right about Tracey when she first appears on screen. I'm very, very attracted to actresses, actors in general, who are not interested in having other people's eyes on them. They’re interested in bringing characters to life. And if they're fighting for something that has to do with their look, it has more to do with the character ultimately and how they should be. And I'm thrilled that I've been able to work with actresses like that. But they're sometimes not A-list, or you know, the ones that get you the money.

ES: Maybe one day Hollywood will catch up with you on that one.

NS: I hope so. There's definitely been strides, and I'm really excited by seeing the diversity in stories. To me, it's a privilege whenever I get to see something that's not like what we're used to seeing. On a bad day, I get cynical and say it's just another fad, you know, how long will this one last? But I really hope that there's enough people, and if enough people jam that door and run through, you can't get them back out again.

ES: I want to talk a little bit about Teresa, Lili Taylor’s character, who wants to become a saint. Cinematic depictions of women devoted to God are usually under the pretext of them being insane and/or manipulative, like in Saint Maud and Benedetta. Theresa's not necessarily either of these things. She's seeking faith in earnest, and you're not judging her for that. Have you seen either of those movies?

NS: I haven't. When I first read the novel, I thought Francine [Prose], how did she know me? Once you get that connection with the character, then there's no way that you can be distant or judgy because you're in it, and you feel at risk, too. I understood everything Teresa did, not to say whether it’s right or what's wrong. I think there were mornings in which she might have questioned her sanity, and moments where she clearly thought she was being told which way to go, one foot in front of the other. I think she carries those two things—that's the tension, right?—within her.

And that happens to all of us. You have a calling or you have a love for something, and you question it for a moment. But then other times, you're so sure and you just keep moving towards it. That resonates for me with filmmaking because my father did not want me to be a filmmaker. I had to have that argument with him, just like Teresa had to have the argument about becoming a nun. So there was none of me looking at her like, Is she crazy? I could hear people around me asking those questions, everybody can look at this movie and make connections in different ways. Then there's that people look at this movie and say, Oh, not for me—like they really don't like it. And I get that, too.

ES: Your father didn't want you to be a filmmaker. I'm curious what did he want you to be. I'm assuming he didn't want you to work in restaurants, either.

NS: No, no, no. I like to psychoanalyze my dad, who's not with me anymore, but I think he took on the role of machismo, but it didn't fit him well. There was a vulnerability; that's where I connected to him, especially as he got older, but he was very clear about what women needed to do or not do. I'm talking patriarchy, like, big time. My mom was a schoolteacher, and when they got married, he said she couldn't teach. My sister reached the sixth grade, and he said that's it for education. But luckily, other family members, mostly women, sat him down and literally formed a tribal meeting and told him his daughter has to continue going to school. When it came time for college, he wasn't interested in education. But that's also a cultural thing: Southern Italians think education, instead of elevating you, takes you away from your people. And in some ways, it does. I don't think he could have ever articulated this. It was just a knee-jerk reaction for him.

ES: That's really interesting about education taking you away from your people and not being able to hold both things at once. It reminds me of the scene with Michael Imperioli’s and Lili Taylor’s characters where she's talking about what she wants to do, and she wants to serve God. And he says you can be close to God and your family. You can serve both at the same time.

NS: You can be a wife and a mother.

ES: Speaking of motherhood, you were pregnant when making this film. The story is a lot about parents and children and these generational curses—was that on your mind a lot?

NS: It wasn't planned to work that way—that I would be that pregnant at that point with that particular story. I'm not that good at manipulating things in my life. [laughs] Francine wrote what is at times such a scary story about pregnancy. Some days I thought, What am I doing? Am I influencing? Very much like the grandmother Carmela who says that if you look at the chickens, you're going to give birth to a chicken. When l was filming and planning and shooting, at times I wondered if I was doing this for protection. So it was a combination of being in this very vulnerable place, but also feeling very strong—because I loved this story, this unusual story, and I just was thrilled to get it made.

Household Saints screens at the 4 Star on Wednesday, January 31st at 7:30PM, with Nancy Savoca in person for a Q&A

Previously: Household Saints opens tomorrow, January 12, at IFC Center, the theatrical premiere of a new digital restoration. Nancy Savoca, Michael Imperioli, and writer/producer Rich Guay will be in attendance for a Q&A at tomorrow evening’s screening. On January 13, there will be a Q&A with Savoca and Guay.