A bright red AstroTurf field intersected by prismatic geometries fills the center of a massive room like a modernist rug. Above, a three-sided jumbotron hanging at midfield and four LED screens at the corners broadcast a five-channel, hour-long video that keeps time with cuts to a play clock. Next to the field, a simulacrum of an announcers booth bears silent witness, with a storyboard of photos and archival materials arranged on an interior wall. Nearby, a rectangular trench cut into the floor reveals engineered strata and toxic sludge below. This is Matthew Barney’s new installation, Secondary (2023), shot in his Long Island City studio and now on view there.

In American football, the secondary is a group of defenders who play furthest from the line of scrimmage, targeting opponents who make it past the primary defenders. On August 12, 1978, the most feared of the Oakland Raiders secondary, Jack “The Assassin” Tatum, delivered a shattering hit on New England Patriots wide receiver Darryl Stingley, rendering Stingley paralyzed from the neck down and initiating NFL reforms regulating on-field conduct. This moment of impact and broader choreographies of masculine violence and transformation are the subjects of Secondary.

Recruited to Yale in 1985 to play football, Barney was a star athlete before he was a star artist. His early Drawing Restraint work (1987–ongoing) developed a performance art practice from athletic approaches to movement and strength training rooted in rupture. Physical restraints and the push and pull of body and architecture are throughlines from the artist’s collegiate work to his most recent production. In both, Barney breaks something in order to make something. For the publication that accompanies Secondary, Barney recalls his earliest memories of football practice in Boise, Idaho. Lined up in opposing groups, the teenaged boys were instructed to run at each other and ram helmets. “I remember seeing stars walking back to the end of the line, and I couldn’t wait to do it again,” the artist reminisces, before noting that “recent research into athletic head injury and the consequence of repeated micro-concussion makes those memories more complicated.”

The Cremaster Cycle (1994–2002) was Barney’s first cinematic foray into the pageantry and schematics of football and the male anatomy. Blending dance with competition and cosmogony, the earliest films were demented science fiction and madcap occultism, focused more on union and fusion than fracture. Here and in Secondary, Barney’s trademark “field emblem” figures prominently. An ellipse or pill form with a bisecting horizontal bar, the heterosemic pictograph is both orifice and closure, representing control over an organic system.

Secondary is a restaging of the Tatum-Stingley hit and a material-based choreography of fitness and madness where the studio is a central character. As with much of Barney’s work, exacting visions of the personal and mythological unfold alongside committed ball play. At Metrograph for a recent screening of Cremaster 4 + 1, the person next to me remarked on how gay the work is. Does focusing on sanitized testicles make the work gay? Initially considered queer for his transgressive use of Vaseline and high heels and for occasionally showing his genitals, Barney’s work can now be more easily understood as being about men rather than being gay. An unsilenced phone in the Cremaster screening rang out with the ESPN chime.

In Secondary, Barney himself plays Raiders quarterback Ken Stabler while legendary movement artists David Thomson and Raphael Xavier star as Stingley and Tatum, respectively. Barney as Stabler falls or otherwise bashes his skull in multiple scenes, and at one point takes out the soft plastic padding from the inside of his helmet and tapes it to the outside, causing impacts to be even more damaging. The quarterback-director-artist is fucked in the head, and the facepainted fans are screaming banshees. Raiders owner Al Davis is portrayed as a geriatric boogeyman, pushing a rusty walker around and smelting rage and muscular aspirations for undead devotees. Objects resembling barbells are cast in a bioplastic used in medicine to regrow bone, evoking injury and recuperation.

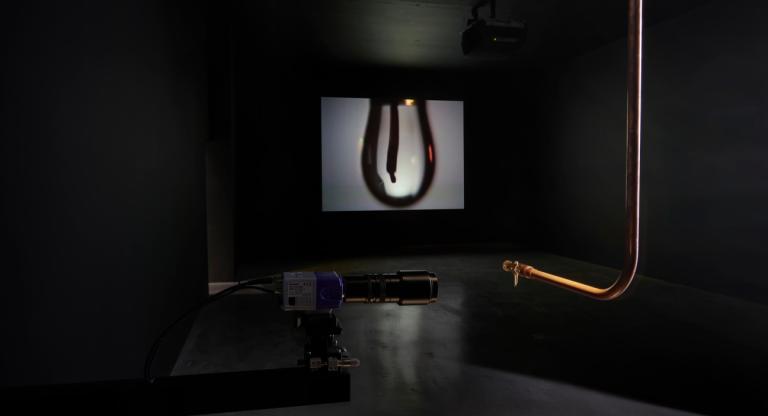

Materials common throughout Barney’s work (lead, aluminum, self-lubricating plastic, and terracotta) are all present. They bend, ooze, and break to extend the performers’ gestures and retain our attention on the uniquely American alchemy of extracting profit from pain and spectacle from violence.

Secondary runs through June 25 at Matthew Barney Studio. It is accompanied by screenings of The Cremaster Cycle at Metrograph, running through the week of June 5. Matthew Barney will be in conversation with the writer Maggie Nelson on June 4.