Is Danny Glover the devil? That’s not not the foremost contention of writer-director Charles Burnett’s To Sleep with Anger (1990), whose title, in transposing Ephesians 4:26’s familiar counsel—“do not let the sun go down on your anger, and do not make room for the devil”—to the present infinitive, suggests an ambivalent contemplation of the Faustian bargain, wise to its pull as well as its peril.

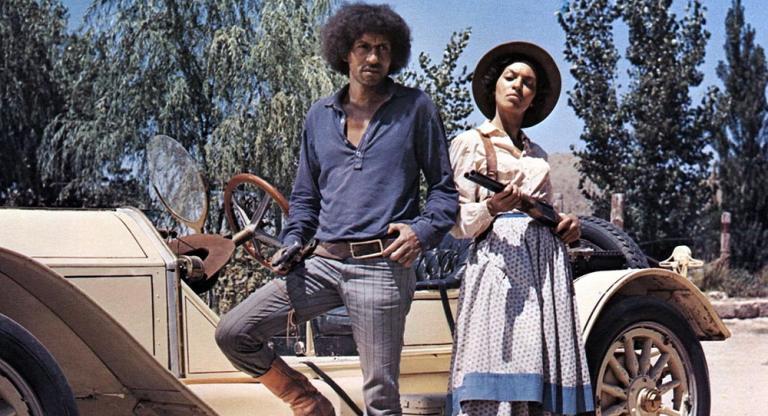

Glover is Harry, an old family friend who drops in on Suzie (Mary Alice) and husband Gideon (Paul Butler) at home in South Central Los Angeles. Like the prowling Uncle Charlie in Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt (1943), Harry’s sudden, sustained presence both vitalizes and unsettles the family: conjuring bygone rural charm while inflaming preexisting tensions, especially between Suzie’s two grown sons, Junior (Carl Lumbly) and “Babe Brother” (Richard Brooks). Even their names gesture toward the film’s expansive rendition of kin; from its earliest scenes, less important than precisely who “belongs” to whom is that all these children, wives, and neighbors comprise a precious network, the seams of which Harry—lone as he is—can’t help but probe for weakness.

On its surface, To Sleep with Anger is most glaringly “about” the milieu of Black migration from the American South to Watts, Los Angeles, where Burnett moved from Mississippi with his own family, and where he set both his lyrical thesis film Killer of Sheep (1978) and lesser-seen follow-up My Brother’s Wedding (1983). Here, too, from the confrontation between folkloric wisdom and Christian values, we get tradition and modernity in irresolvable tension. But there’s another tension shaping the film, as aesthetic as it is narrative, that recalls Buñuel’s Los Olvidados (1950) in its uneasy composite of naturalism and surrealist eruption. To Sleep with Anger was Burnett’s first shot at a “big” budget with a box-office star—and the film is anchored by Glover’s sensual performance, at once lascivious and menacing—but there’s also, still, a distinctly poetic hand at work: in the camera’s talismanic attention to objects, in the conveyance of red from a brake light’s flood to a screaming kettle, and in visions like the one that opens the film, where Gideon dreams himself not so much bursting into flame as persisting with his own slow combustion.

Stubbornly evocative, To Sleep with Anger sidesteps the undemanding lessons of a cautionary tale, showing its characters the very care they so pivotally, and memorably, extend to one another.

To Sleep with Anger screens this evening, December 2, with a Q&A with Danny Glover, and on December 7 at Film at Lincoln Center as part of the series “Danny Glover and Louverture Films.”