Johan Grimonprez’s new documentary, Soundtrack to a Coup d’État (2024), is an educational film. I do not mean this in a pejorative sense, but only to remind the film’s viewers that most of the great historians actually committed to elucidating the Western world’s crimes over the course of the last century have been independent artists. This is the case with novelists like Don DeLillo and Thomas Pynchon whose satirical bite holds more truth than any mid-century reportage. But this is also the reason why films such as Chris Marker’s Grin Without a Cat (1977)—a four-hour vision of mid-century leftist organizing across the globe—remain fringe objects. As works authored by dissenters, the former’s novels and the latter’s film, are persistently sidelined in culture at large. That the conspiracy behind the assassination of the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s first Prime Minister, Patrice Lumumba, has never been as clearly told as Grimonprez manages in Soundtrack to a Coup d’État—more than sixty years after its occurrence—is surely a triumph for the filmmaker, but it is also, more sorely, a sad reflection of our nation’s unwillingness to acknowledge its crimes while hoping they fall into historical oblivion.

Grimonprez’s new film assembles archival footage, sound-bites, and jazz extracts to show how the United States and Belgium, alongside other Western nations, plotted a coup in the newly independent Congo and then assassinated its leader: Lumumba. Central to Grimonprez’s telling of this story is the United States’ deployment of jazz ambassadors like Dizzy Gillespie and Louis Armstrong to promote capitalist agendas in non-aligned states like Yugoslavia, Indonesia, and Egypt. Per Gillespie, it was the “Cool War” not the Cold War. But to the greater irony behind the United States’ employment of Black musicians to extol their nation’s virtues abroad while contending with the Civil Rights Movement within its own borders, Grimonprez makes a point of featuring Armstrong saying, “We all felt like Lumumba was right.”

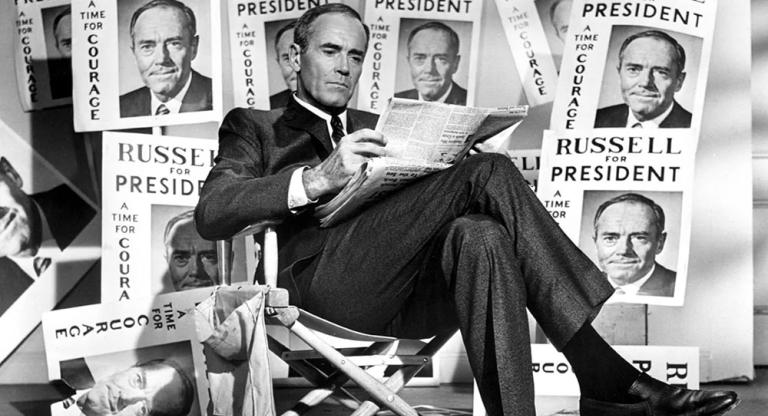

There’s a moment in Soundtrack to a Coup d’État when Armstrong realizes that his performance in Leopoldville is being used as a smoke-screen for CIA operatives to coordinate the extraction of uranium from the province of Katanga, which had recently seceded from the Congo; naturally, he’s enraged. Grimonprez’s decision to disclose Armstrong’s rage, as well as the CIA’s shady tactics, exemplifies his film’s aim to make known that which has been historically suppressed. And it is for this reason that so much of the film revolves around meetings at the United Nations, which are in themselves representations of diplomatic chicanery and political shenanigans. As a work committed to disclosing all of the secrets and lies involved in keeping imperial nations and their capitalist underpinnings alive, Grimonprez’s film makes excellent use of archival sources to bring forth political transparency where none has existed. But it is Soundtrack to a Coup d’État’s inclusion of Tesla and Apple advertisements—two companies reliant on the extraction of rich minerals from the Congo—that is even more striking because it indicates the issues in the film are not dead, but have simply been shirked.

Soundtrack to a Coup d’État screens tonight, April 25, at BAMPFA as part of the San Francisco International Film Festival. Director Johan Grimonprez will be in attendance to receive the Persistence of Vision Award.