The problem with G.W. Pabst's (German) version of The Threepenny Opera is that, really, it condemns nothing, it suggests no alternatives or "forms of resistance", and it is beautiful. This is no problem at all for any number of great works of art—think of a painting of a dining room table by Bonnard, or one of Joseph Cornell's boxes—but everything about the film's distinctly Weimar depictions of a corroded London society of beggars, prostitutes, bands of thieves, and pitifully corrupt officials, demands that it should and must be a political film.

For those familiar with Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weil's wildly popular theater piece of the same name, much will be recognizable. This is still the story of the dandy prince of thieves Mackie Messer and his midnight marriage to Polly Peachum, who, it turns out, is the only daughter of the notorious Beggar King of London. When the Beggar King seeks revenge, Mackie runs, Mackie seduces, Mackie is caught but escapes with the help of Jenny, his favorite prostitute and capricious guardian angel—while in the meantime Polly and the rest of Mackie's gang learns the valuable lesson that it's more lucrative to own and operate a bank than to rob one.

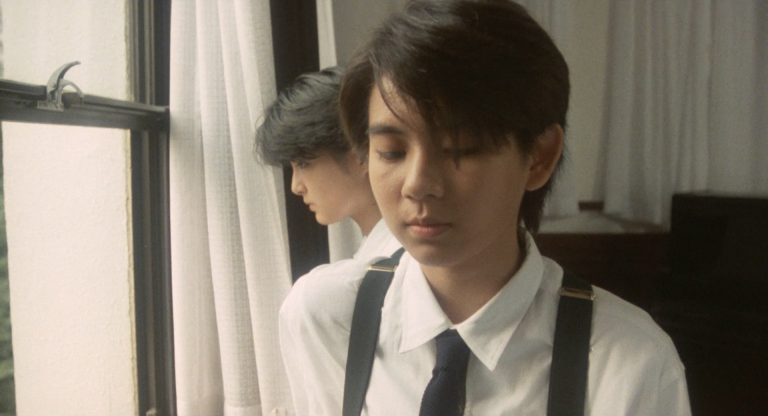

Brecht and Weil had conceived of their play as a political re-appropriation of bourgeois opera for the purposes of popular art. But it is clear that Pabst and his employers had no such ambitions. Instead of Brecht's incisive critique of capitalism's inherent duplicities and criminality, Pabst offers us opera. For nearly two hours we drift from scene to scene, largely oblivious to time and where we are, and what motivations these interchangeably glamorous and ugly people have for doing the vile things they do. Every image of Rudolf Forster as Mackie is seductive. And even when he flippantly admits to having seduced two underage girls, or treats Jenny once again as a mule for kicking, we find his absolute and willful amorality charming.

We find it all charming and beguiling and utterly mysterious, partly because the film's gauzy black-and-white images transfix the underground bars, brothels, and dirty back lanes into its own dream language; but also, because, unmoored from any kind of dialectical opposition, the film's characters are free to be disgusting and beautiful without complications.

The result is uncanny. It is certainly a masterpiece as a work of art. But it's a masterpiece whose beauty and magic is inseparable from its wickedness.

The Threepenny Opera screens Thursday, February 13, at BAMPFA, as part of G. W. Pabst: Selected Films.