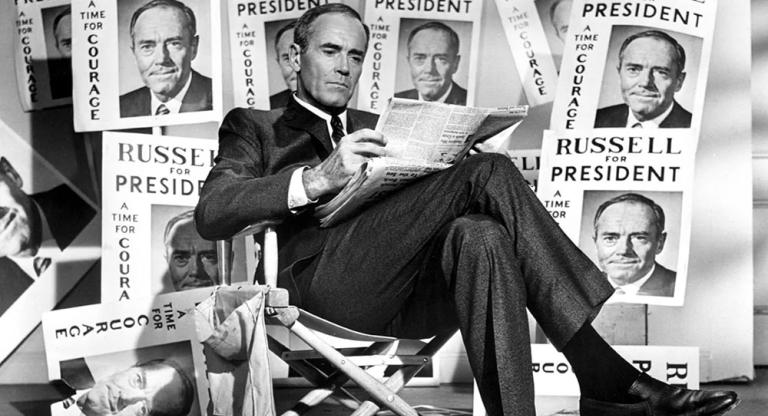

Scripted by suspense novelist Leonardo Sciascia and directed by Elio Petri, Todo Modo is a political tract fitted into the framework of an occult murder mystery. Set in a spiritual retreat in the countryside where Italy’s reigning political elite comes to be purified and legitimized, the film focuses on the tribulations of “il Presidente,” an obvious stand-in for then-president of the Italian Christian Democrats, Aldo Moro. Portrayed with malevolent relish by frequent Petri-collaboratorGian-Maria Volonté, the Moro character caused the film to be pulled from circulation following the real Moro’s execution by the Red Brigades in 1978. Although Volonté has said that his mannerisms were modeled on those of several influential politicians, his self-effacingly lowered head and his meek smile make the reference to Moro unmistakable. Michel Piccoli (Themroc, La Grande Bouffe) plays prime minister Giulio Andreotti (referred to only as “Him”), while the retreat’s leader, Don Gaetano—who guides the assembled politicians through their Loyolan spiritual exercises—is played by Marcello Mastroianni (The Organizer, La Grande Bouffe) with such intensity that his first sermon almost turned me into a Jesuit.

Petri’s leftist credentials were established over the course of his career with films like The Working Class Goes to Heaven and Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion, while those of Sciascia came from a career in institutional politics. In 1975 he was elected to the Palermo city council on the Communist Party ticket and remained a member until his resignation in 1977 over the Historic Compromise, the coalition government formed by the CP and the Christian Democrats. Sciascia too had already made his mark on Italian cinema with adaptations of several of his own novels: for Petri’s We Still Kill the Old Way (1967), Damiano Damiani’s The Day of the Owl (1968), and Francesco Rosi’s Illustrious Corpses (1976).

Petri and Sciascia’s choice of the Christian Democrats as the target of their satire was not a casual one. They both saw the DC as a continuation of the values and principles of Fascism beyond the end of Mussolini’s reign, and the party’s development in the 60s and 70s as a symbol of a gradually decaying political culture, blighted by hypocrisy and mediocrity. Although Todo Modohas often been perceived as an allegory shrouded in complex symbolism (The New York Times‘ Vincent Canby called it a “surreal fable”), Petri intended it as a straightforward polemic, calling it “a pamphlet in which I violently express my—and not only my—thirty years of rage against Christian Democracy.” Sciascia also clearly felt the film—especially its ending—to be much less enigmatic than its critics did. He describes the finale in the corpse-littered forest surrounding the retreat as the moment when “the justice-wielding proletariat becomes a sort of exterminating angel.” Is Aldo Moro’s deferential chauffeur (played by Pasolini’s one-time favorite lead man Franco Citti) a personification of the silently suffering proletariat, and is his shooting spree its long-awaited vengeance?