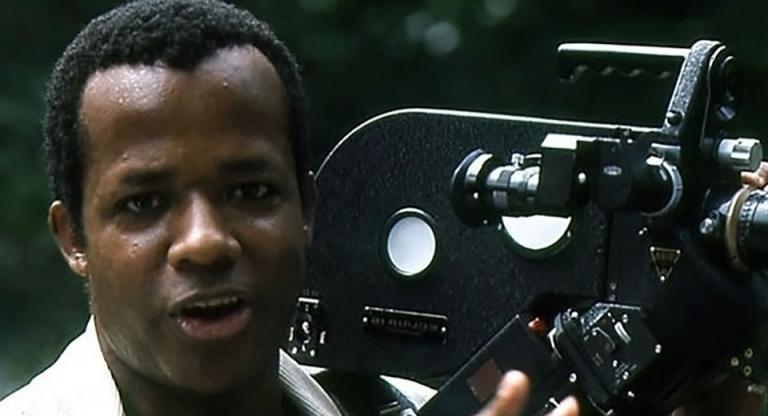

Silence is an obstruction to be rapped through in Marlon Riggs’s tour-de-force essay film Tongues Untied (1989). Initially conceived as a short documentary on gay Black poets, the project splintered when Riggs tested positive for HIV during production. It expanded to become a stunning mix of documentary, music video, scripted feature, performance, poetry, and art film.

When publicly-owned stations in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and New York City broadcast Tongues Untied in 1990, audiences saw a romantic same-sex kiss for the first time on American television. PBS sought to present Tongues Untied nationally the following year, but opposition erupted from those who preferred to keep tongues tied. Dozens of local affiliates chose never to screen the film or programmed it near midnight to minimize visibility.

Responding to the brouhaha caused by “moral censors” and “would-be guardians of American culture,” Riggs made clear that the film “was motivated by a singular imperative: to shatter America’s brutalizing silence around matters of sexual and racial difference.” Tongues Untied announces urgently that “Black men loving Black men is the radical act” and also considers the thin membrane between pleasure and death: “Now we think as we fuck. This nut might kill.” Tongues Untied was filmed when AIDS, homophobia, and white supremacy wrought a devastating cocktail. Riggs and many of his co-performers died from AIDS in the years following the film’s release.

The poet-activist Essex Hemphill, Riggs, and others look past their mortality straight into the camera, speaking of their desires and resistance. We hear their heartbeats. Footage of drag balls and queer liberation marches transmits the hypnotic power and self-actualizing beauty of dance and community. A humorous bit from the fictional Institute of Snap!thology demonstrates variations on the finger snap (“the sling snap,” “the point snap,” “the diva snap”), and we learn how snaps function as communication and self-expression in a constrained society. These sequences remind us of the stakes of living truthfully, out loud, in a world whose structures of power expect blank faces and dead silence.

“Anger unvented becomes pain unspoken becomes rage released becomes violence cha-cha-cha.” Voices double and then triple, edited into a polyrhythmic meter like incantation and instruction. Among many highlights in Tongues Untied is the sound design. At times the soundtrack could be an avant-garde vocal performance and at others a public service announcement. Some declamations are repeated by multiple voices at different speeds that swarm around and at first obscure but ultimately clarify each word: “100% off all Black men today. Every day.”

In his February 1990 essay “Street Talk / Straight Talk,” Samuel R. Delany wrote about “the current discourse of AIDS . . . a demonstrably murderous discourse, vigorously employed by the range of conservative forces promulgating the anti-sexual stance that marks so much of this era.” Delany predicted that “a later age will look back on this one . . . with the kind of mute horror with which we read the anti-semitic rhetoric that proliferated through Germany in particular and Europe in general all through the ’30s and ’40s.”

Tongues Untied is an important document for us to look back on, and we should turn up the volume as we do. It amplifies the horrors of living in a homophobic and racist culture while also, as Riggs says, refusing to “present an historically disparaged community on bended knee, begging courteously for tidbits of mainstream tolerance.” These men vogue, sing, snap, kiss, caress, educate, march, and speak back at the hatred that comes their way from all sides. They love each other and encourage each other to tell of their love. Delany is on the same page when he insists that the only way to “destroy the discursive disarticulation that muffles and muddles all” is “not to interpret what we say, but to say what we do.”

Riggs’s film does this work. In his words, Tongues Untied is an “uncensored, uncompromising articulation of an autonomously defined self and social identity.” As social identities become further digitized, commodified, replatformed, flattened, and neutered, Tongues Untied sears with a bruised but optimistic queer vitality, obliterating illusory distinctions between fiction and non-fiction, documentary, portrait, or testimony. The film’s blaring honesty has not quieted over the years, and will continue to expand and mutate for generations to come.

Tongues Untied screens tonight, July 12, and on July 17, at Anthology Film Archives as part of the series “Let’s Talk About Sex.”