On the surface, Hollywood’s two adaptations of Liam O'Flaherty’s 1925 novel The Informer – set a scant three years after the Irish War of Independence – have more differences than similarities. John Ford’s eponymous 1935 version follows disgraced IRA-member Gypo Nolan as he weighs the betrayal of his lifelong friend, noteworthy rebel Frankie McPhillip, against the life-saving prospect of a £20 bounty. Centuries of English occupation have sentenced Nolan and his comrades to a lifetime of half-personhood, destroying any legitimate avenue for autonomy and prosperity within their own homeland. The worsening catastrophe that drives Nolan to his unspeakable act is not unique to Ireland’s fearless rebels: per Shakespeare, borrowing from St. Augustine, “there is nothing new under the sun.” In Jules Dassin’s 1968 political thriller Uptight, our own shameful past provides an updated backdrop for this enduring moral tale.

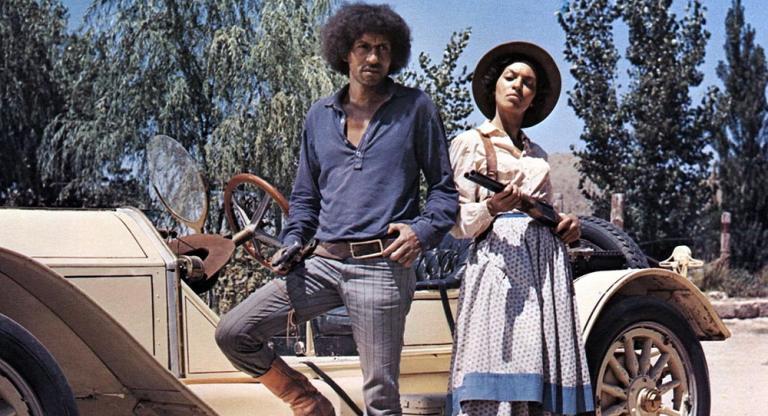

The kinetic screenplay, by co-stars Ruby Dee and Julian Mayfield, transports O’Flaherty’s still-timely story to another milestone in America’s unfinished Civil War. What begins as a moment of national mourning — Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s murder at the hands of terrorist James Earl Ray – lights a fuse of revolution that persists to this day. Trading Dublin for an increasingly de-instrualized Cleveland, Uptight follows one-time steelworker Tank – played by Mayfield in his first on-screen leading role – on a hell-bound journey from hopeful activist to reluctant stool-pigeon. For his friends and neighbors, Dr. King’s assasination is a wake-up call, revealing firsthand the limits of non-violence. Tired of working in the white man’s factories, rotting in the white man’s jails, and living off the white man’s crumbs, the city’s rising Black Power movement takes up arms and prepares for retaliation. For Tank, this drastic strategy inspires only disillusionment, effectively sending him down a road to ruin from which there is no return. Credit is due to Dee and Mayfield for depicting this capitulation not as an act of cowardly surrender but an unnavigable pact with the devil, born from a desperation that would consume even the most stalwart revolutionary.

Uptight marked Dassin’s return to American filmmaking after a two-decade absence, his exile the result of a notoriously racist, antisemitic, and anti-labor witch hunt by the House Un-American Activities Committee. Dassin was never shy about his affiliations: he was an alumni of the radical Camp Kinderland, a getaway for young leftists, and a card-carrying party member from his early days in the Yiddish theater. After 20 years in Europe, his eventual collaboration with co-writer Mayfield was, in many ways, preordained, echoing their respective experiences with undue persecution. A towering figure in New York's post-War theater scene, Mayfield’s career was summarily cut short as a result of his associations with fellow travelers Paul Robeson and activist Louis Burnham. The black mark on his political life even resulted in a sizable FBI file – one that would later be used to justify a trumped-up kidnapping charge in 1961.

Uptight places Dassin’s courageous refusal to “name names” and Mayfield’s legacy as an outspoken crusader as symmetrical lives on two sides of the racial divide. Whether their shared place in this dark chapter led the pair to a 40-year-old Irish novel, the connection is clear. From Dublin to Cleveland, wherever the state exerts its might over the dispossessed, you will find young men, beaten down and desperate, caught in an inescapable trap between privation and the lucrative double cross.