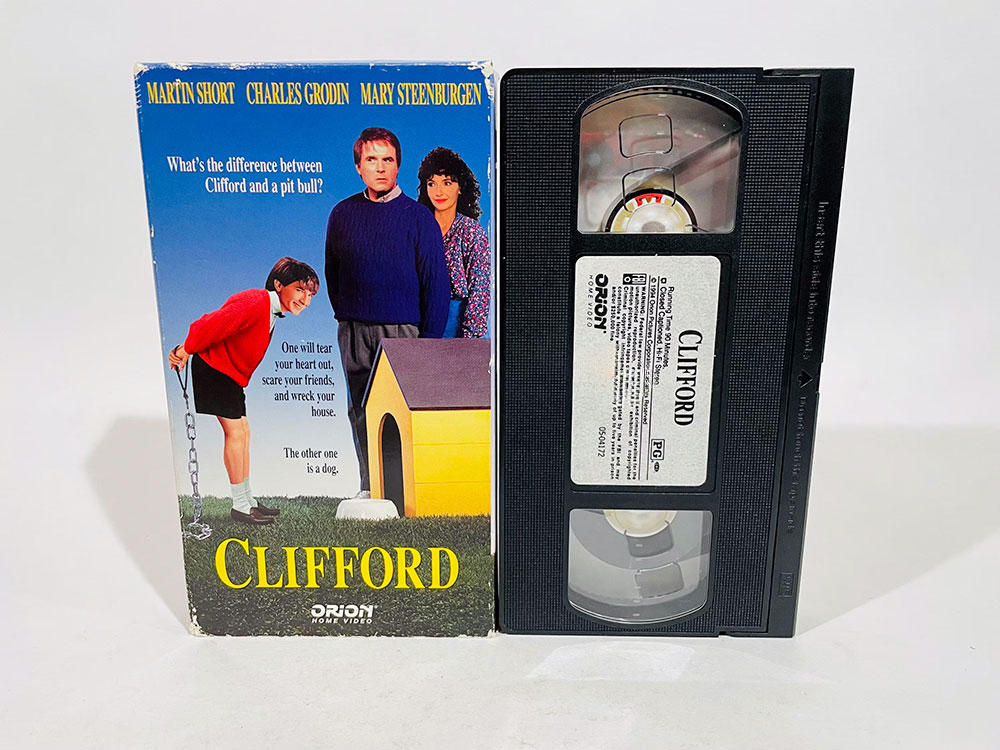

Our copy of Clifford was kept in a plain brown hard plastic case. It bore no image from the film or promotional copy, just the title and year on a typewritten label, which gave it an austere dignity that belied the mayhem within. Our mother had bought the tape from the local video rental store when they had gone out of business and liquidated inventory. For years we kept it just on top of the VCR, for easy access. It was one of the few things on which my siblings and I could all agree: Clifford is funny.

Martin Short plays the title character, a ten-year-old boy visiting his uncle Martin (Charles Grodin, in all his ill-tempered glory), who promises to take him to a certain Los Angeles theme park that Clifford regards as Mecca. When Martin’s demanding work schedule intervenes, that promise is broken, tensions escalate, and finally the standard adult policy of alternating containment and appeasement is abandoned in favor of total war.

When we tried to talk to our friends at school about the movie they naturally thought we meant the Big Red Dog, which was frustrating at first but gave our repeat viewings a clandestine air: Only we know about this. It wasn’t until much later that I met anyone else who had seen the film; at the time, few people had. After disastrous test screenings and reshoots, its release had been delayed for three years while Orion Pictures went through bankruptcy proceedings. When Clifford finally did come out the critics lit into it—“irredeemably not funny,” Roger Ebert’s half-star review crows—and audiences stayed away.

The press seemed to regard the premise of a grown man playing a young boy as a deplorable grotesquerie. As children, I’m sure we didn’t think much of it. Short’s narrow face, ruled by its mouth, is quite convincing atop a prep-school blazer and shorts. We knew he wasn’t really a kid, but then we didn’t really consider ourselves kids either, but rather prisoners awaiting emancipation from our parents. We understood something of this spirited boy and that faraway look in his eyes. Here was another Home Alone–style saboteur-savant, though while neglected Kevin McCallister must defend himself against enemies from without, Clifford rages against the family itself, tragically aware that he is too strange to be loved by them.

The project was developed as a comedy version of The Bad Seed, Mervyn LeRoy’s 1956 drawing-room drama, in which Patty McCormack plays an eight-year-old girl who shares many of Clifford’s attributes—precocious, ingratiating, grimaces when pawed over—but departs from him in her appetite for murder. Clifford’s actions are extreme, but nonlethal and not exactly psychopathic (not to say that some diagnosis wouldn’t be proffered today). His reign of terror is justified by the righteous angst of preadolescence: “It isn’t fair. They’re never fair.”

Like so much great art, Clifford was misunderstood and maligned in its own time, left to the discount bins where a family like mine could find it and give it the home it deserved. Short’s ragdoll physicality takes off from his Ed Grimley character, the gyrating hayseed with teeth set on edge, and prefigures the creation of Jiminy Glick, that fabulously voluminous truth-teller. He and Grodin play the two-hander with evident zeal, never better than when they are competing for the affections of Mary Steenburgen’s tender and credulous Sarah Davis. Richard Gibbs’s score exalts the action at every turn. Richard Kind and Jennifer Savidge make a brief but indelible appearance as the boy’s parents. And it’s very, very funny.

On the occasion of the film’s 30th anniversary—celebrated with a cast and crew live 35mm screening at BAM Saturday presented by Hollywood Entertainment—I spoke with Martin Short and Paul Flaherty, the film’s director, about improvisation, whether making a comedy has to be serious business, and both men’s obsession, when they were Clifford’s age, with Hollywood and the Stars (1963–64), the short-lived NBC supercut documentary series that provided a film education in 30-minute intervals.

Maxwell Paparella: Clifford is a landmark film of my childhood. It’s a real privilege to be able to talk with you both about it.

Martin Short: You clearly had a very troubled childhood.

MP: You know, I'm getting the sense that it was based on having looked over the critical response to this film, which of course I had never seen or been interested in before. So I didn't realize that no one got it—

MS: No, they didn’t.

MP: —or that people thought that Uncle Martin would have been justified to murder Clifford.

MS: That's absolutely correct. Yeah.

Paul Flaherty: Roger Ebert did not get it at all.

MP: Do you think he might have been sore that you'd killed him off just a couple of years before in your HBO special [I, Martin Short, Goes Hollywood, 1989]?

MS: It's true. I did. No, I think that truthfully—I remember Mitch Hurwitz said this to me once about Clifford. ’Cause he was a big fan, and he was always amazed at the initial reaction. But he said it's like shows like Arrested Development. Certain shows are playing to a kind of very odd and, I presume to say, hip and evolved group. And sometimes it takes time for others to catch up. It's kind of fascinating, actually. It released in ’94, but it was made in 1990.

PS: Because Orion went bankrupt right after we finished it.

MP: And that can be hard for a comedy.

MS: Exactly. It can be. Bankruptcy and comedy. Actually, with the exception of Trump. But other than that, it’s hard for a comedy.

PF: But, you know, the impression was that the movie was shelved. Because it didn't come out, it didn’t come out, and years went by. And people just thought, Oh, boy, it must have been so bad that they couldn't even release it.

MS: A lot of people did not enjoy that film or get that film. But, again, tastes change through the years. Three Amigos [1986] was another film that had wildly mixed reviews, and now they want to put up monuments [to it]. So I just think it's always interesting, particularly with comedy: what ages well and what doesn't. I mean, I can still look at Young Frankenstein [1974], and I think it's literally perfection. And I feel that about Annie Hall [1977]. There are certain films that just have never been altered by time. And some have become less funny with time, and some become funnier.

MP: Well, this is one of those films in the first group for me. I started watching Clifford when I was Clifford's age. When I rewatch it now, I find it essentially intact from my memories. Although one thing has changed: I now relate more to the character of Uncle Martin.

MS: Of course.

MP: I sympathize with him in my adult life in the way I originally sympathized with Clifford, and still do in many ways. I wanted to ask about your relationship to these characters and how Clifford was developed. Did you intend for him to be pure evil, à la The Bad Seed?

MS: Well, certainly The Bad Seed was an influence. Patty McCormack at one point says, “Oo, I like that.” So we deliberately had Clifford say, “Oo.” Things like that.

PF: The Bad Seed was always one of your favorite films.

MS: The perversity of it, yeah.

PF: You were always quoting lines from it. I always felt that that was a real motivating factor for you, to do a comedy version of The Bad Seed.

MS: The reality was that Steven Kampmann and Will Aldis came up with the idea and approached me about it. So it did not start with my thinking about it. They had this idea, and an early script of the idea of this kind of problem child. And then it was Steven Kampmann’s idea to have me play it. And I thought that was kind of insane. But we did a screen test, and it was really funny. So from that Orion committed to the film.

MP: And then it took a few twists and turns as it moved through production, and Kampmann, who was supposed to direct, came off the project, and you came on, Paul. And then I understand there were some rewrites.

PF: Yes, there were substantial rewrites. Marty was spearheading the rewriting of it.

MS: I remember that Will and Steve were now not doing the film. And Larry Brezner, the executive producer, who was my manager, hired Paul to rewrite the script. Paul and I had had such a long history, from SCTV to specials I've done for Showtime and HBO. And the feeling was— Paul, I remember you saying like, “I can't write this without you in the room, being part of it.”

PF: We rewrote it over at your house. But once we were in the room, and once you started to really flesh that Clifford character out, I mean, you know, the best thing I can do is just get out of the way half the time and let you improvise it. You know?

MS: Well, I think you're being a little overmodest—but sure, I'll take it.

MP: How much improvisation was happening in front of the camera? I’ve heard that Charles Grodin liked to improvise.

MS: Absolutely. Absolutely. Absolutely.

PF: Yeah, Chuck was obsessed with improvising at that point.

MS: Yeah, he loved keeping it very loose and very free. He loved “freedom takes” and “loose takes.” And he was hilarious. I mean, he just loved the whole bizarreness of this project. He just fell for it right off the bat.

PF: Chuck did not even want to do a read-through. He didn't like rehearsing it. He just liked getting the freshness of it every time. But, you know, compromises had to be made in that area.

MS: I mean, we did have a script that we tried to follow. Chuck appreciated the idea that you had to always respect the work that writers had put into creating a script, but then he liked to play around with it. And certainly, the more playful he got, those were the— I mean, it's hard to remember. You’d have to look at dailies with a script beside you to remember what ended up in the film: Was it a more improvised take, was it a less improvised take? But certainly, he liked to keep it loose. And he had a very, very brilliant mind when it came to comedy.

!["[Charles Grodin] had a very, very brilliant mind when it came to comedy."](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Clifford-1994-Martin-Short-Charles-Grodin-2.jpg)

PF: The two of you together, Marty, you being the best improviser I've ever worked with. Getting the two of you in the scene, you know things are gonna get improvised to some degree in most takes. Although I remember times that you and I had worked writing a scene, crafting a scene, and Chuck would come in in the morning and would have completely rearranged things. And we would say, “Chuck, we worked all day on that damn scene.”

MS: [Charles Grodin impression] “All right, we’ll try it your way, and then we’ll maybe play around . . .”

PF: He would ask things in a completely straightforward way. If he had a take on a scene or a line, and if I or Marty had a different take on it, Chuck would say, “And you think that's funny?” He was actually asking a question.

MS: Yes, that’s true. [Grodin again] “I don’t see it, but that’s fine . . .”

PF: He was also the only actor I've ever worked with who asked me to give him a line reading. I can't remember what the line was, but I was dancing around it so I wouldn't give him a line reading. And he just sort of watched me dangling around, and he said, “Just do it for me.” So I did the line, and he said, “Okay. I got it.” That’s the only time that’s ever happened to me.

MP: This is a film that could have easily leaned on its physical humor. It could have been just its premise, which is that Clifford is a ten-year-old boy being played by a 40-year-old man. But there's a more psychological through line, as well.

MS: I was 40, and there was no getting around it. But we did try. The designer would make buttons on his vest bigger. Obviously, there was no CGI, but everything was done to help play the premise that I was this 10-year-old boy. And it was very important to me that he was 10, because I felt that he had to be prepubescent, you know?

PF: And that’s hard when you’re 40.

MS: Yeah, for some, I guess.

PF: When we were shooting this Marty just teased me mercilessly every day. If you asked him if he preferred to have sex or tease me, he’d say, “I'll get back to you.” He just loves teasing me. But I would also tease him.

MS: Of course. You'd say, “He may be a ten-year-old, but with a 40-year-old neck.”

PF: You hear people say—comedy people—that if you're having fun on a set or laughing then you’re making a lousy movie. You know, I think that's bullshit.

MS: I totally agree with you. It's totally garbage. I mean, I do this show [Only Murders in the Building] that Steve [Martin] and I are doing. All that everyone does is laugh. If I were doing a comedy, particularly, and it was a tenth of that, I would personally completely freeze up.

PF: Me too.

MS: To me, a set should just be laughs and loose. And all Steve and I do all day is just insult each other and make fun of each other. And now Selena [Gomez] is into it, and she's learning how to do it. And everyone laughs all day long. And I think that's imperative in a comedy.

MP: You’ve often found humor in the tawdry and workaday aspects of show business, but those gibes always seem premised upon a deep love for the industry, and especially earlier traditions. I think of you as kind of a late vaudevillian, really. When did that interest begin?

MS: It's something I always loved, still love. As a kid, I was fascinated by the Rat Pack—Sammy and Frank—and I used to have an imaginary television show in my bedroom when I was 15. And I would type things up for TV Guide, you know, in my imaginary world. It was just something I loved. As a Canadian, not living in the United States, it never felt like anything realistic. So it wasn't like I was in Manhattan and my parents would say, “Well, you should audition for the National Theatre School, or try to get into NYU.” I was going to be a doctor. But then I realized it was just because I was a fan of Richard Chamberlain's work; it wasn't because I cared about science. And then in university, I started to do more and more [acting]. And then I took this year off from being a social worker and tried to be an actor. But I always loved the idea of show business. It seemed like so much fun.

PF: Marty, when you were a kid, did you watch Hollywood and the Stars?

MS: Oh, I was obsessed with Hollywood and the Stars. In fact, the theme to Hollywood in the Stars—

PF: [humming] Dee da dum, dee dee da dum . . .

MS: —was the theme that Paul Shaffer played me out with on Letterman for 40 years. Because Paul was obsessed with it as a kid in Thunder Bay, Ontario. We were both 11 or 12. And just the idea of “Hollywood and the Stars, narrated by Joseph Cotten.”

PF: That's right. And eventually Henry Fonda took over, remember?

MS: That's right.

PF: In Pittsburgh, my brother Joe and I were doing exactly the same thing. Watching that show every week. And every time I heard that theme it would tug at me. And I was just wondering if one day I'd win an Oscar, you know?

MS: That theme was Elmer Bernstein, by the way.

PF: Was it? Good theme, because it never leaves your memory.

Tonight, March 29, Topos Too and Hollywood Entertainment present “The Kid Stays in the Picture,” a symposium of readings and performances on the theme of adults playing children featuring Jon Dieringer, Caroline Golum, Elizabeth Purchell, Jourdain Searles, and more.

Clifford screens tomorrow, March 30, at BAM, presented by Hollywood Entertainment and supported by Screen Slate. Martin Short, Paul Flaherty, Steven Kampmann, Richard Kind, and other guests will be in attendance for the early screening, and Short will introduce the late show. Screen Slate members receive a $5 off discount.

Many more tales from the production and aftermath of the film can be found in Rob Turbovsky’s 2021 oral history of the film.