Moving images take center stage at this year’s Whitney Biennial, which the press release frames as a multimedia “examination of reality.” Even Better Than The Real Thing affords generous space to the many videos on display in stand-alone viewing rooms or embedded in hybrid installations. Many of the works tend toward didactic exposition, not without creative flourishes but altogether more rote than revelatory. It’s as if “the introduction of machine learning models to daily life and media,” which the curatorial text warns about, is degrading artists’ abilities to make concise work that can speak beyond generic conceptual prompts. Inconsistency notwithstanding, the best videos in the exhibition are sublime and elliptical artworks that engage the technologies of language and labor as well as the “impact of war, dictatorships, colonialism, and the resurfacing of lost cultural histories.” These videos stand on their own merits and in open-ended chains of kinship with other works in the exhibition.

Richerche: four (2024) by Sharon Hayes emulates an open classroom. Assorted chairs and a bench surround a two-channel video featuring conversations about gender and sexuality. The work is crisply edited and its overhead speakers amplify humorous and revealing insights among queer elders. If the conversations preach to the choir, the video’s rhythmically shifting gaze and the interviewees’ friendliness implicates visitors to the gallery into an open-hearted mode. When the chairs are empty, the work assembles with nearby medicine cabinet sculptures by Carolyn Lazard and drawings on vellum by Mary Kelly, synthesizing the sense of the gallery as a learning environment.

Rather than share territory with its neighbors, Diane Severin Nguyen’s In Her Time (Iris’s Version) (2023-2024) exists in its own world; it is fully enclosed with custom curtains, cushions, and a metacinematic narrative. In Nguyen’s piece, an actress documents herself preparing for a role in a historical war film and navigating a massive studio full of sets and props. In Her Time is one of three works in the exhibition with a runtime that exceeds 60 minutes; museum visitors can remain comfortably prone on red mattresses, following the journey between the war film’s stagings, the actor’s reality, and the reality of the museum, where the tear gas profiteer Warren Kanders’s name still graces the main stairwell.

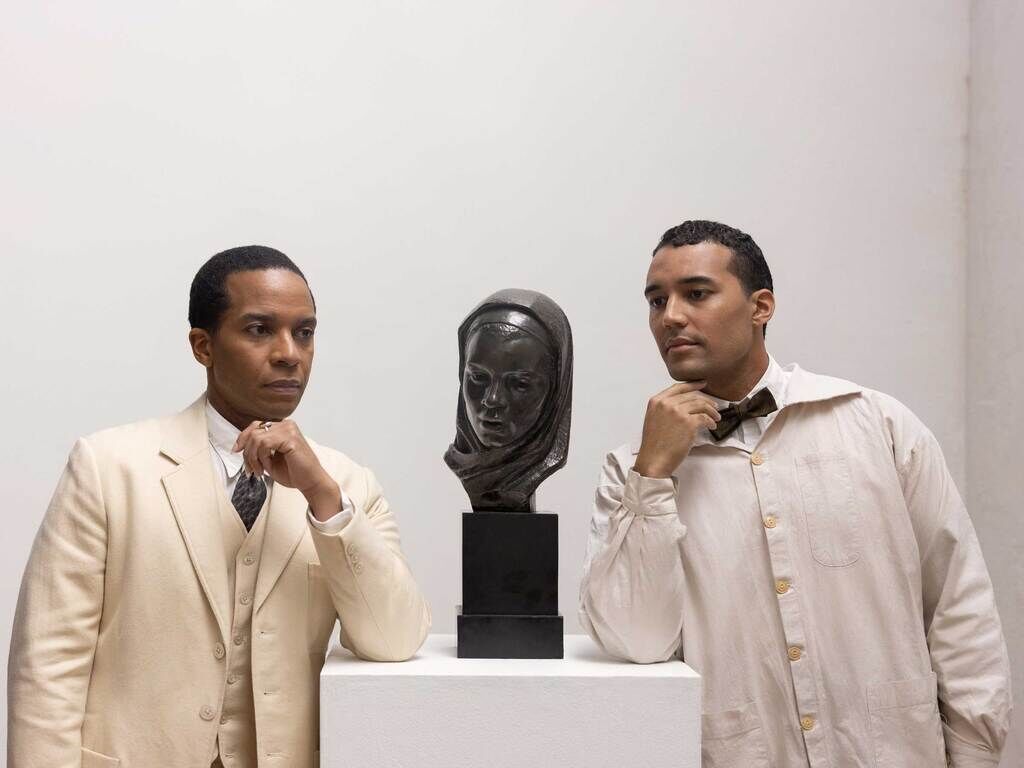

Isaac Julien’s Once Again… (Statues Never Die) (2022, pictured at top) unfurls within mirrored interior walls and an installation of sculptures by Richmond Barthé and Matthew Angelo Harrison. Presented as a five-channel black-and-white video projected upon irregularly spaced and freestanding screens, the work is a tour-de-force that transforms a conversation between the Harlem Renaissance bard Alain Locke and the Philadelphia art patron Albert C. Barnes into an immersive cinematic poem. Here, lineages of objects and people fuse not in declarative sound bites, but in full-bodied compositions that one can curiously meander around as they play out.

Dora Budor’s Lifelike (2024) dispenses with voiceover and speech altogether, instead taking an iPhone mounted to a gimbal on a tour of the shimmering, soulless surfaces of contemporary art and architecture in Hudson Yards. The would-be smoothness of the footage is roughed up by a blur that the wall text reveals is the result of a vibrator strapped to the camera. Even without knowing the pleasure-device is the cause of the blur, the manically distorted views of glass-and-metal façades transmit the intense emotions sublimated in these spaces, from Equinox to the Edge. The staircase to nowhere at the center of Hudson Yards is filmed from ground level by Budor, owing to the structure being indefinitely closed after multiple people took their own lives after scaling it. A few blocks away, Budor’s camera captures Charles Ray’s new steel public sculptures: Adam and Eve (2023) resolutely hold court at the foot of a new luxury commercial real estate enterprise.

On screen and elsewhere in the museum, along the High Line and beyond, there are always new technologies accelerating extraction and consolidating power. The curatorial text for Even Better Than The Real Thing harps on this, focusing on AI as if it were a new concern that artists such as Shu Lea Cheang and Lynn Hershman Leeson have not been reckoning with in their work for decades. In many ways, this focus on machine learning feels like a diversion. The word “genocide” does not appear anywhere in the press release, nor do the words “oligarch” or “billionaire.” We must continue to question artworks and other cultural materials, noting how artists or curators may be simulating one conversation to avoid another.

Whitney Biennial 2024: Even Better Than the Real Thing is on view through August 11 at The Whitney.