Zach Clark comes out of, and works within, two distinct traditions in low-budget filmmaking: the rough-and-ready, accessible-digital, no-budget independent scene, and the exploitation film. Stories of elder-millennial angst with a seedy edge, his films are cheaply made and stylishly edited, with the same jazzy giallo flair he brought to the cutting of films like Sophia Takal’s Always Shine (2016) and (Screen Slate’s own) Caroline Golum’s A Feast of Man (2016).

Starting in the mumbly, flat-lit, visibly zitty 2000s, Clark’s films have traced a satisfying arc of emotional maturation, beginning in quarter-life ennui and emotional messiness, and opening out into considerations of monogamy, family, and even parenthood, beginning with 2009’s Modern Love Is Automatic, about a bored nurse who moonlights as a latex-clad dominatrix, through the girls-weekend acid freakout Vacation! (2010), 2013’s blue (blue as in sad, blue as in Sarno-adjacent suburban swinging) Christmas movie White Reindeer (2013), and 2016’s Brody-approved ragtag humanist ensemble piece Little Sister. This evolution continues in the gross, but very tender retro B-grade sci-fi The Becomers (2024).

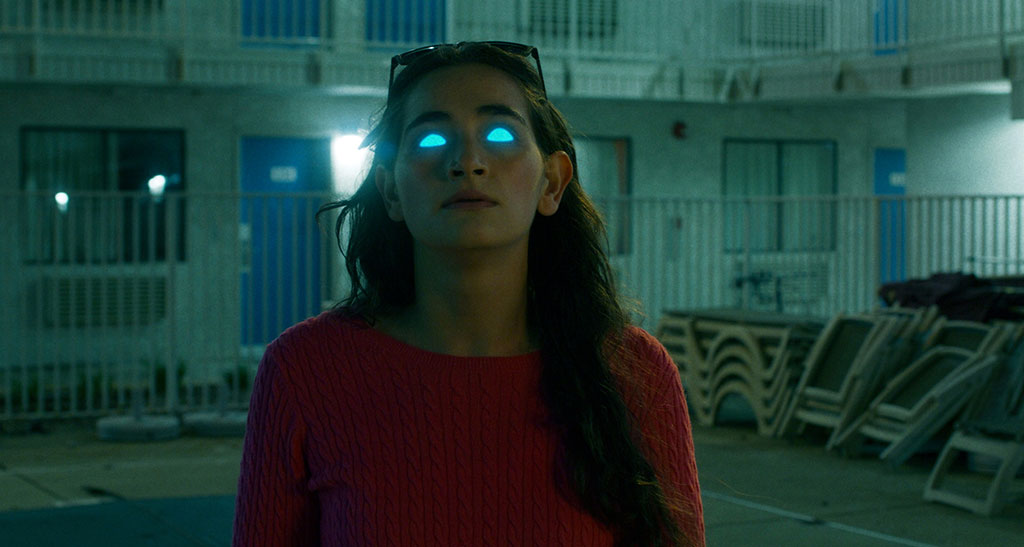

Inspired by a prompt, from producers Joe Swanberg and Edwin Linker, to make a low-budget genre movie, the film was written in a hurry, its script serving as a dumping ground for Clark’s feelings after a year or so of lockdown. Russell Mael of Sparks narrates the film as the voice of a glowing-eyed alien life form who falls to earth, an escapee from their dying home world. The planet they find is hardly more hospitable; as the alien jumps from host body to host body—spending the longest time in the vessel of a militant Covid-truther played by Molly Plunk—they acclimate themselves to the pandemic’s new abnormal, defined by bad vibes, heightened paranoia, and the white noise of TV reports on the kidnapping of a blue-state governor.

The film complicates the relationship between the gendered body and identity; the alien pines after their lover, who has likewise arrived on our planet in a pink escape pod and likewise shifts through several shapes over the course of the film (disposing of used-up bodies with a regurgitated acid bath), on their way back to the being who feels like home.

I met up with Clark earlier this August in Union Square to discuss his film. It was the end of the workday; the greenmarket was packing up, a young couple made out on the lawn, and the air was vibrating with the rhythm of distant drumming and ripe with the scent of nearby garbage.

Mark Asch: I'm curious about doing Invasion of the Body Snatchers [1956] as a pandemic allegory, because one of the things I love about the original Don Siegel Invasion is the double-edged political allegory: is it a metaphor for commie infiltration and flouride in the drinking water? Is it a metaphor for Red Scare paranoia and conformity? Is it neither? Is it both? And similarly, with this one, is this a metaphor for right-wing brainworms, or mind-control nanobots in the vaccine, either, neither?

Zach Clark: During Covid, the virus was a little bit scary, but other people were especially scary—everyone became a source of danger during that time. I never think of the aliens themselves as a metaphor in this movie. I think of the aliens as a conduit to explore these different things that were happening. And the things that were happening are like: the alien meets a weird, lonely incel, then gets in with a QAnon-pilled suburban couple, and then a corrupt politician in the process of being me-too’d.

But it did feel like moving from body to body, and having bodies be so central, was a way to explore the mania of that time.

MA: There are elements of that time that also resemble a grade-Z ‘50s sci-fi movie. Trump-world is a motley collection of weirdos, like Ed Wood’s stock company.

ZC: The world sort of became a science fiction movie for a year.

MA: And everybody was experiencing exposition entirely through janky screens. If you remember the ‘52 Invasion, U.S.A., not the Chuck Norris one, it’s a communist invasion of America that's mostly stock footage, except for people in a bar reacting to the exposition coming through the media to them. You do fun stuff with TV in this one.

ZC: One of the most fun things we did on this was making that fake reality dating show. If you're an alien who comes to Earth… When I watch those shows, they feel alien to me. What planet am I on, and what planet are these from? Same thing with Fox News, which I find endlessly fascinating. Usually when I have access to cable, I will go to Fox News very quickly, because it is just so bonkers to watch. It strikes me that television news and reality shows are a very uniquely American medium.

MA: Speaking of restricted locations, this is a very pandemic movie in the sense that a lot of it is contained within a single house, but that’s also very much a micro-indie thing, to rent a house and make a movie about millennial couples going on vacation together. The Airbnb indie.

ZC: I'm editing a movie right now that's an Airbnb movie…

I’ve done those before. The house in Vacation! is my dad's beach house, the house in Little Sister is our producer Melodie's parents' house. A lot of locations are just what was available. So Eric Ashworth, who's one of our executive producers on The Becomers, that's his house, the suburban house, and the basement is his mother-in-law’s basement.

My favorite location in this entire movie is the Motel 6. It's the closest I've ever felt to shooting on a soundstage, because everyone had their own room. Camera had a room, production had a room; we got a costume room and a makeup room, and it felt very organized and professional.

My budgets have stayed roughly the same, so I usually find myself in a similar situation. But this is the first time I've ever shot a movie with scenes in a motel where the motel knew we were shooting the scenes. There's scenes in the lobby and stuff. They all knew we were there. They're all very nice. We paid for those rooms and everything. It was all aboveboard. Every other movie that has a scene at a motel was just I'm just gonna rent a room in this motel. I can do whatever I want to, I'm paying for it.

MA: When you're making a reference to something, let's say, The Man Who Fell to Earth [1976], how digested by the movie do you want it to feel? Is part of the pleasure for the audience, in your mind, not just seeing it and thinking, “Oh, this is a good moment,” but also recognizing, “Oh, this is The Man Who Fell to Earth”?

ZC: Well, my counter to that is, what moment are you talking about?

MA: The reveal that the aliens have no genitals, they’re completely smooth down there.

ZC: Oh, right, right, right. Yeah. That is Man Who Fell to Earth.

So, this movie was made so quickly that it has very few references. I didn't watch a lot of things going into this movie, it was just ‘60s Star Trek living in my brain. I think I watched I Married a Monster from Outer Space [1958] and a few other ‘50s sci-fi movies, just to look at coverage, how spare coverage was. But I didn't watch other science fiction movies in this vein, and then make one. I love Man Who Fell to Earth. I love Roeg’s work, Bad Timing [1980] especially, so, it's all in there.

There is certainly more direct, intentional lifting in other movies. In Little Sister we literally show things on the TV. Here's Carnival of Souls [1962]. There's The Wizard of Gore [1970]. In this, they watch The Creation of the Humanoids [1962], mostly because it's public domain and fun and sort of tangential. But I was really just trying to live in the general spirit of something.

MA: All of your features have, up to now, have had female protagonists. This one doesn't, but it still uses what we might call an alien perspective.

ZC: I've always said, I'm not really the person who can answer this question. I’ve always done it because it feels right—the work I've always been drawn to is work that has female protagonists. In the script, the alien is called “they,” but I think in the first draft that that central alien was called “she,” because it felt natural for me. The filmmakers I’ve always been drawn to, including John Waters and Fassbinder and Chantal Akerman and Douglas Sirk, all center the female perspective. But there isn’t an, "I do it because…" Everything I've ever done is about myself. And maybe part of it is that that level of remove allows me to get in, in different ways.

MA: I'm curious about how the infrastructure that supports your films has changed, in terms of getting funding, getting stuff shown, whether that's at festivals, or theatrically in New York or elsewhere, or streaming. Because we can look back on the 2000s—these new digital cameras have just hit the market, South By Southwest is still a film festival and not a national-security job fair—in some ways it seems like… I don’t want to say it was a golden age. But I’m curious whether it’s gotten harder or easier.

ZC: Little Sister, we were blessed. That movie really couldn't have had a better production, post turnaround, critical reception, release. That movie made its money back within a year of premiering on the festival circuit.

And similarly, I couldn't have asked for anything better for the previous one, White Reindeer. IFC released that movie; again, the critical reception was phenomenal. The financing of White Reindeer was done through Kickstarter, and it was designed to not need to make its money back. The Becomers was traditionally funded. We would love it if it made its money back. But, again, I know that this is a very strange, scrappy movie, even in my own filmography; we’ve found ourselves in a not dissimilar place from where we were with Vacation!: it's a little too out there for the traditional indie market and a little too indie for the genre market. People who like my other movies tend to like it, so there's at least a throughline there.

MA: Modern Love, did that play at the reRun Gastropub Theater?

ZC: Yeah, Vacation! did too.

MA: I will explain that to our younger readers in a parenthetical. [In the late 2000s and early 2010s, the leading American showcase for micro-budget filmmakers was SXSW, whose main venues included the Alamo Drafthouse, then a regional phenomenon. The reRun, in the back of a Dumbo events venue whose owner eventually went to jail, was an early attempt to transplant the dine-in theater phenomenon to NYC, and programmed largely films from the post-mumblecore festival circuit.] And those films would get reviewed in the Village Voice, places like that. If that's the baseline expectation for a filmmaker in your niche 15 years ago, where are we now compared to that?

ZC: On the whole, I feel better about the prospect of getting a movie seen now than I did fifteen years ago. But I think in the middle of those fifteen years I felt the best about it. Does that make sense?

MA: So like, immediately pre-pandemic?

ZC: Yes. For example, both White Reindeer and Little Sister were on Netflix for three years, and what that did for the exposure for those movies... White Reindeer was made for under $100,000, Little Sister was $225,00. The idea that a movie like that would be on Netflix or a similar platform… and certainly I wasn't the only person whose work was being disseminated in that way. That era feels like it's not here anymore; the avenues that are available are more plentiful, but smaller. They're paying less money (which is, I think, fine; they pay what they can for these things).

MA: Staying on the subject of low budgets, a lightning round about resourceful filmmaking. The aliens’ glowing eyes, done digitally in post: it must have been a real pain in the ass to have the glow flick on and off every time an actor blinked.

ZC: That's our VFX artist Josh Johnson, who did an incredible job, and yes, took on the task of having to do those blinks every single time. There's shots that hold for a long time in this movie with the eyes.

Because we made this movie so quickly, we—in a good way and a bad way—didn't have much time to think about how complicated some things would be.

MA: And the bile, the acid that the aliens vomit, what is that?

ZC: It’s pudding, like vanilla pudding with food dye in it. Thinned out with water a little bit, but pudding gives you that viscous quality.

MA: You've used a lot of pop songs as score in the past. Less so in this one, which features music by Fritz Myers, who’ll perform live at the Spectacle screenings in September.

ZC: We knew going in that we would need a lot more music to tell the story. The alien is in sunglasses half the time, and acting in a stilted way. Fritz always does gorgeous, incredible, beautiful work, but I knew he was going to need to help me a bit more on this one. We wanted an expansive, cosmic feeling to it. A lot of early Devo, a lot of Throbbing Gristle, that's what we listened to, to prepare for it. And then he came up with the idea to use a vocoder.

MA: I always write down when I watch a movie—

ZC: If there's a vocoder in it?

MA: No, my favorite credit, in the end credits, whether that's “drone pilot” or “on-set medic” or, in the case of your film, “alien vocalization,” I believe, is the credit?

ZC: Fritz not only used a vocoder in the score, but all of the sounds that aliens make were designed by Fritz. And we had all that stuff going into production, so the actors were all lip-syncing to those sounds.

MA: Will the performance lean more toward alien vocalization?

ZC: We're conceiving of the vibe as: What does a dying planet feel like? What are the sounds of a dying planet?

The Becomers opens on Friday, August 23 at Cinema Village, and August 24 on VOD. It will also screen at Spectacle on September 6 and 7, on both nights preceded by a performance from composer Fritz Myers and followed by a Q&A with Myers and Clark. The film will also be presented with a musical performance at the Roxy on September 11 and Nitehawk Williamsburg on September 23.