In their debut feature film, brothers Adam and Zack Khalil richly synthesize an astonishing array of materials over the course of a brief 69 minutes. INAATE/SE/ [it shines a certain way. to a certain place./it flies. falls.] is a retelling of the Seven Fires Prophecy, a foundational spiritual narrative of the Anishinaabe peoples; a portrait of Sault Ste. Marie in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, and the Ojibway Natives who have lived in the area since long before there was a Michigan at all; and a wide-ranging political essay.

The filmmakers traverse this varied terrain by an equally varied assortment of methods—interviews, animations, staged fictions, narrated capsule histories, expressionist montage, and détourned museum videos, to name just a few. Ojibways who grew up in Sault Ste. Marie (a city they depict with dreadful beauty), the Khalil brothers address their film directly to tribe members of their generation, here cast as the prophesied redeemers of a culture that has been kept alive against the most violent efforts to suppress it. “Whenever we share something with non-natives,” a Midewiwin practitioner reminds viewers, “it’s theirs. They take off with it.” From its title on down, INAATE/SE/ is an act of polemical self-representation.

At the same time, the Khalils do the patient, maddening work of contextualizing and explaining their tribe’s history in a manner accessible to a variety of audiences, inevitably including those who number among Native Americans’ most vicious and incurious persecutors. The film’s heroes are extended no less complexity than its villains. Ojibways are never exceptionalized, but shown with familiar good humor. Their tradition is not caricatured as an immutable set of truths handed down by revelation, but taken as ever-evolving social practices whose continuity cannot be repaired by preservation, only elaborated through struggle, and finally achieved under conditions of genuine self-determination.

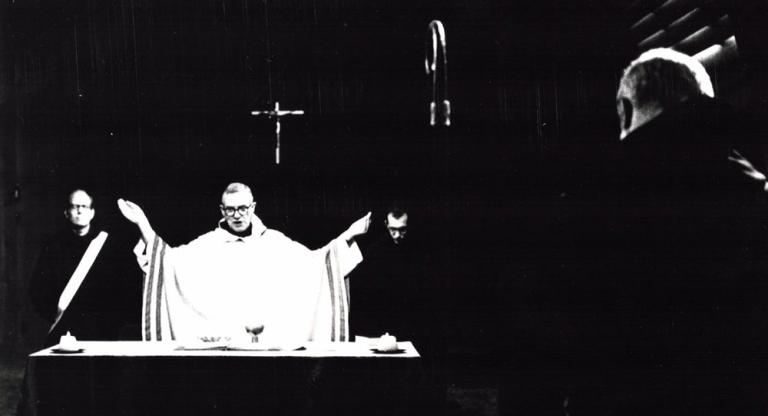

Much of what has been stolen from the Sault Ojibway by the local agents of the American project is displayed in a bizarre monolith that looms over the town called the Tower of History, which houses a museum that pays tribute to Jesuit missionaries, and attends to Natives only as long vanquished adversaries. Early on, the film sets its sights on history in this sense as one of its targets for destruction. But nothing in INAATSE/SE/ is so straightforward. Though the Khalils assault the settler mythology with tools drawn from ritual, religious fable, and mystical vision, it is primarily through history in its fuller meaning—the ordering of fact to clarify the overriding determinations that have made the past, and which structure the present—that they indict the ceaseless brutality of American settler-colonialism, and celebrate the creativity of the Ojibway people.

The film is by turns warm with human love and icy with studied hatred; soberly responsible and uproariously perverse; gently didactic and vehemently defiant. Confident in its antagonism without ever lapsing into smug self-regard; formally adventurous but never esoteric, INAATE/SE is an inimitable model for what radical documentary in the 21st century might be.