More than once in Catherine Breillat’s Abuse of Weakness we find ourselves staring at a body writhing helplessly on the floor. The body belongs to Isabelle Huppert in the role of Maud Schoenberg, a film director, whose life is irrevocably altered by a cerebral hemorrhage. Suddenly half of her body is paralyzed; she is “half a corpse” by her own estimation. And, in spite of her instinctual perversity and desire for laughter, it is impossible to ignore that Maud’s predicament—that is, her suddenly intractable physical condition—has tilted her thoughts inextricably toward death.

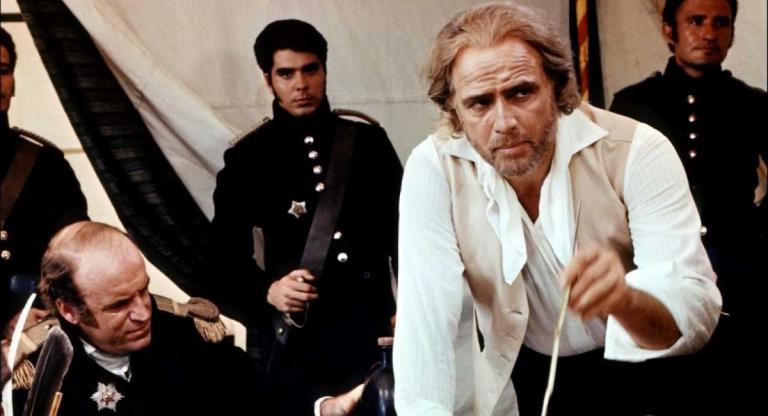

Then one night she sees Vilko Piran (Kool Shen), a self-proclaimed thief and celebrity swindler who she glimpses promoting his “memoir” on late-night TV. Immediately she decides to cast him as the lead in her next film, an idea that both her assistant and her producer try to dissuade her from. But after their initial meeting, where Vilko refuses a screen test and claims to steal all of the books that he reads, it becomes clear that Maud is hooked on his presence. When she then begins to write Vilko checks to cover his “debts” and keep him out of prison, the obvious conclusion is that a shameless criminal has picked his softest target. However, as is usually the case in Breillat’s films, the obvious conclusion is only the oblique surface of a deeper moral puzzle.

Like her most explicit visual reference in the film—the 17th-century French painter Georges de La Tour—Breillat’s gaze is always crystalline, as if the air inside every frame were perfectly clear, and every figure perfectly defined. But, as with La Tour, this precise visual definition is in contrast to the emotional ambiguity of every scene. With complete clarity we see Maud’s and Vilkos’ inconstancies and moral uncertainty. We can spot tenderness and fear and flashes of cruelty in both of their eyes, just as both seem to be living in varying states of illusion. The question, then, is where do these illusions end and the blame begin? But even the film’s damning final scene remains ambiguous enough to acknowledge that, even when we despise and are appalled by its consequences, often these kinds of deceptions are what we desire most—an idea that places Breillat’s film somewhere beyond the personal act of indictment of either the criminal or the artist that it could so easily be mistaken for.