The North of Ireland’s political horizons, culture, and day-to-day life have for more than a century been defined by a struggle that has been raging since long before the administrative invention of Northern Ireland in 1922. Its most famous and bloodiest expression has been the Troubles, a guerrilla conflict lasting from the late 1960s until an inconclusive “peace” was brokered in 1998. Fought between Irish republicans, U.K. loyalists, and the British military, it was the long-simmering outcome of British settler colonialism in Ireland and subsequent years of systemic repression and impoverishment of the North’s largely Irish-identifying Catholic population. Armed struggle also flared as a response to the brutal state crackdown on the Northern Irish Civil Rights Movement, which had led a popular, non-violent struggle throughout the ’60s.

The Troubles penetrated global consciousness despite the best efforts of a powerfully reductive image machine; mainstream print and television in both Britain and the South of Ireland heavily censored their reportage, delivering terms and images tailored to engender only the most reductive ideas about the conflict. Against this image regime, there exists a counter-canon, assembled by filmmakers from Ireland, north and south, such as Pat Murphy and Dónal Foreman, as well as those from abroad. The Black and the Green (1983) is a unique example of the latter. In a gesture of transatlantic solidarity, it links two civil rights movements in an atmosphere of alternating enthusiasm and ponderance. It is a deeply introspective work about how one’s political commitments can rebound and transform as they extend past the borders of one’s own struggle.

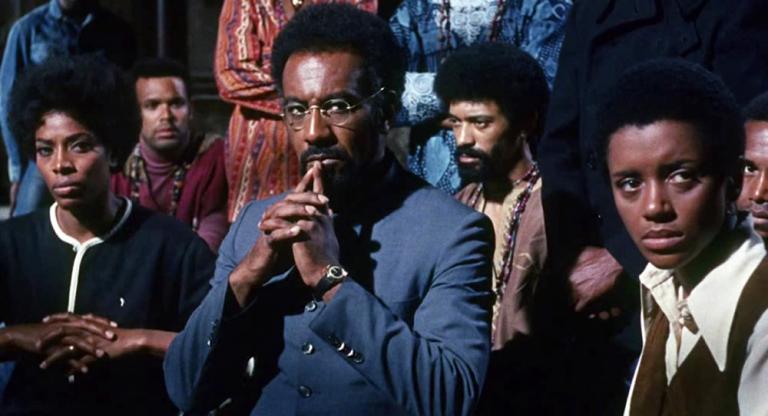

Directed by St. Clair Bourne, the documentary follows a contingent of Black American civil rights activists on a mission of self-education and support to the North of Ireland in December 1981. Their trip was catalysed by the events of that gruelling, flashpoint year. It was organised by the H-Block Committee, a network of international organisations formed in support of those Irish republicans imprisoned at Her Majesty's Prison Maze, the notorious H-Blocks, who led a hunger strike over the British government’s refusal to grant them political prisoner status. The strike ended with the state unmoved and ten prisoners dead of starvation, though the visibility of their protest led to a global outcry, placing the republican cause more firmly on an international anti-colonial stage.

The visiting activists represent a range of organisations, from Matt Jones, formerly of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, to the journalist Jean Carey Bond, an editor at Freedomways magazine. They’re united by their deep commitment to fighting inequality and the power structure anywhere, and a desire to uncover parallels between Black and Irish anti-colonialist struggles. “Black and green” solidarity has a long history, such as Frederick Douglass’s tour of Ireland in 1845-46, although in the U.S. in particular, it’s checkered by white supremacist politicking and disruption.

Bourne records the trip in what at first seems like a straightforward travelogue fashion, with didactic narration from Carey Bond. The film begins stateside before landing in Dublin Airport, where the combative attitude of a southern Irish reporter adds the first complicating wrinkle to the group’s knowledge of the situation. They proceed up North, where they visit the cities of Belfast and Derry, as well as the H-Blocks. They are accompanied by republican spokespeople, and also the less affiliated—victims of police and military brutality, a hunger striker’s mother.

The film’s didactic mien is subverted when Bourne acknowledges the challenge with which the visiting activists are faced, having to grapple firsthand with a deluge of testimonies, new histories, and unfamiliar contexts. The form and shape of the film itself becomes increasingly non-linear and speculative. Bourne intersperses their travels with scenes in which they mull over the implications of what they’ve learned, in the context not only of the North of Ireland but of their own political beliefs and activities back home. These scenes are strengthened by their staging: the casual monologues are delivered facing the camera, against a blank background. The sense of intellectual fermentation and of mutable political consciousness broadens the film’s scope. More than just the record of a political mission, it is a philosophical work about the nature and process of international solidarity and of radical, grassroots political action anywhere.

Eventually, a debate over the use of violence as a fundamental revolutionary praxis becomes the explicit crux of the film. Jones states that his belief in non-violence is shaken, not knowing whether they can rightfully criticize the use of force in a situation through which they are only passing through. As they become more immersed and overwhelmed, many of the Americans start to wonder if violence becomes inevitable in any grassroots political struggle.

The film’s climactic moment is one of triumphant solidarity, a group-singalong at a Belfast community center, led by the visitors, to the tune of “We Shall Overcome.” If more questions than answers arise in the course of their trip, they are questions which should trouble the heart of every revolutionary.

The Black and the Green screens through July 13 at BAM in the program The Black and the Green + the Films of St. Clair Bourne