I’m a sucker for weekends in coastal Maine—eating lobster rolls and blueberry crumble to the sound of buoy bells and seagulls—so when the Camden International Film Festival rolls around each fall I’m eager to pack my Aran sweater and hit the road. This year, though, I decided to skip the seven-hour drive and enjoy the fest’s offerings remotely from the comfort of my home. Most of the 18 features in Camden’s virtual festival are accessible by purchasing a $100 virtual pass, but a handful are geo-restricted to New England.

Emilija Škarnulytė’s Burial is a haunting meditation on humanity’s long-term relationship with nuclear power, specifically on the daunting challenges of dismantling a massive nuclear power plant. The Ignalina plant in eastern Lithuania, eight miles from the Belarusian border, was built in the late 1970s as a “sister” to the plant in Chernobyl, Ukraine. When Lithuania applied for accession into the European Union in 2003, its membership was predicated on decommissioning the plant by 2038, a process that is currently in full swing. A number of on-screen texts inform us that 3,544,000 cubic meters of concrete and 108,000 tons of equipment have to be removed by 2038, making the task totally unprecedented in human history. Once that is achieved, we are told, the problem will be where to store the radioactive waste. We are taken on a tour of the intended long-term storage site: a network of deep shafts straddling the Meuse and Haute-Marne départements in eastern France, where the Kimmeridgian claystone has been deemed geologically suitable for stashing medium- and high-level radioactive waste for the next 10,000 to 100,000 years.

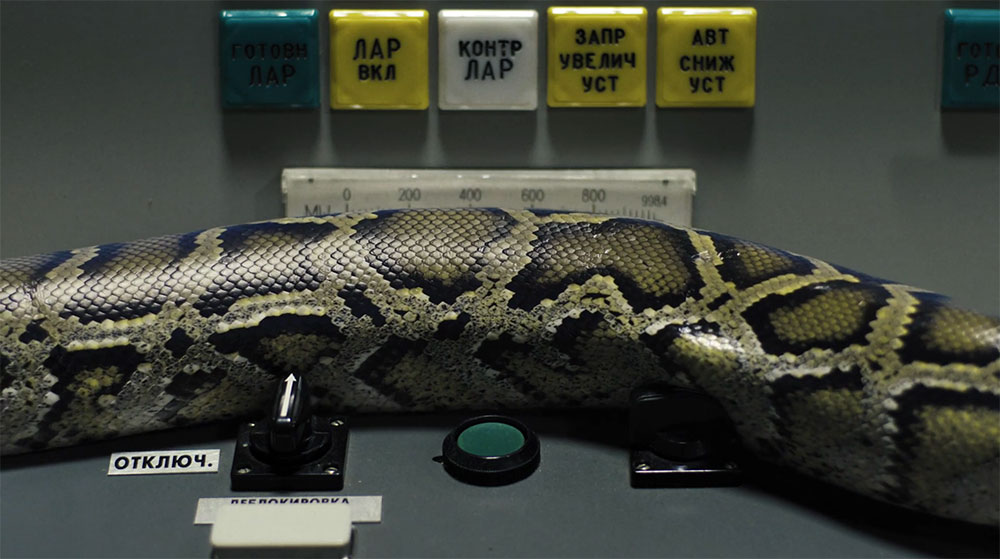

At the risk of sounding basic, the film is hypnotic: slow dolly shots into mineshafts, murky underwater footage of giant anacondas in the Amazon river, static shots of a boa constrictor slowly gliding across antiquated control panels composed of worn plastic dials labeled in Cyrillic script. The interplay between Vytis Puronas’s sound design and Gaute Barlindhaug’s sparse score underlines the desolation of such images as hazmat-clad workers sorting rusty panels on a creaky conveyor belt, layering echoey clangs and howling winds with dissonant electronic drones. Adam Khalil (co-director of Nosferasta: First Bite) served as one of five cinematographers.

The theme of nuclear waste is also taken up in Lily Frances Henderson’s This Much We Know, adapted from John D’Agata’s About a Mountain, a 2010 book-length essay about the Department of Energy’s project to transform Yucca Mountain, some 100 miles northwest of Las Vegas, into a long-term radioactive waste storage site. Henderson’s film simultaneously attempts to shed light on the enigma of suicide by subjecting the story of Levi Presley IV—who died by suicide at 16—to systematic inquiry and finding the places where the scientific method falls short. She interviews a county coroner, who is a real cut-and-dry type, convinced of the reliability of black-on-white facts and intolerant of ambiguity. Henderson also interviews the chief engineer of the Yucca Mountain project, who wholeheartedly believes that “There’s nothing better than to look at the data, postulate why such things are, develop tests to prove or disprove your ideas about it, and then have it reviewed.” The counterpoint to these men of science is Levi’s parents and friends, who are not able to analyze Levi’s death into a set of discrete data points, much less address the unanswerable question “Why?” which hovers over the entire film.

Las Vegas has famously been dubbed the “suicide capital of the world,” with a suicide rate double the national average. Henderson does a pretty decent literature review, citing studies from 1997 and 1998 and a major one from 2008 that found that living in the city increases one’s chances of dying by suicide by 50%. She goes back to the ur-study on the subject, Émile Durkheim’s 1897 book Suicide: A Study in Sociology, in which he postulates the existence of a subcategory of suicide that results from anomie, a situation in which common values and meanings are not understood, leading to social formlessness. Henderson’s film is more successful on the level of content than it is formally; she approaches her subjects with compassion, but the frequent vignetting of the frame and the rapid associative montage at times lend the film an Instagram aesthetic.

The theme of formlessness is reprised in Saudi-American filmmaker Ahsen Nadeem’s Crows Are White (pictured at top), a memoiristic essay film with splashes of observational documentary and talking heads. The film starts in medias res with Nadeem scaling Mount Hiei in Kyoto in search of the famous Buddhist monk Kamahori, whom he wants to ask—implausibly—for relationship advice. (His devout muslim parents live in Ireland and are not aware that, back home in Los Angeles, Nadeem is about to marry his infidel girlfriend, Dawn.) Alas, Kamahori has taken a vow of silence, so Nadeem instead befriends a low-ranking monk named Ryushin who works in the monastery’s gift shop. While the elite monks undertake herculean, eight-year-long ascetic feats, Ryushin is stuck selling tchotchkes and answering phones. But his lowly position makes him more relatable, and Nadeem quickly discovers that Ryushin loves 80s thrash metal and shares his own appreciation for decadent desserts. “Watching a vegetarian buddhist monk eat five pounds of beef and get drunk made me a bit jealous,” Nadeem observes. “Unlike me, he’s comfortable living with his contradictions.” It turns out that Ryushin has turned to religion to give some form to his chaotic life, but he doesn’t let it dominate him.

But Ryushin’s life is not as carefree as it may seem. He is depressed and remains directionless. “I do not enjoy my life,” he confides. “I am ready to die.” His fantasy, to Nadeem’s surprise, is to become a sheep farmer in New Zealand, a wish that Nadeem decides to spend a part of the film’s budget on fulfilling. Unfortunately, Ryushin has no experience with sheep and soon finds himself beating them back to keep from getting bitten. The sequences with Ryushin are by far the film’s most satisfying, as Nadeem’s relationship woes and debilitating fear of his parents’ disapproval soon becomes frustrating and indulgent. The film’s most luscious offering has to be its exploration of the verdant, misty environs of Mount Hiei, shinto spirits tangibly lurking in the trees like in Princess Mononoke.

Exploration of place is also central to Reid Davenport’s I Didn’t See You There, which is an intimate portrait of both the filmmaker’s current neighborhood of Uptown Oakland and his birthplace in Connecticut. Davenport spends a lot of time documenting the blocks around his home: the Oakland School for the Arts; Kaiser Permanente’s brutalist headquarters; and the Tortona Big Top, a red circus tent that Davenport pegs as a visible reminder of the oppressive legacy of the American freak show. On the subject of this legacy, Davenport tells us in voiceover, “I can feel it when I’m stared at and I’m not seen.” For someone who isn’t in his position, this phrase might seem counterintuitive, but I Didn’t See You There gains its resonance from the fact that the entire thing is shot as a handheld POV from Davenport’s wheelchair, putting the viewer in the vicarious position of being openly gawked at by passersby while also being ignored by society. The frustration of being stuck in the street with oncoming traffic because aloof pedestrians are blocking the curb cut, or not being able to cross the street because a group of tech bros are parked in the crosswalk packing the trunk of their Beamer, is palpable. Aesthetically, I Didn’t See You There approaches Brakhage-levels of abstraction, as Davenport frequently points the camera straight down at the pavement while zooming along on his motorized wheelchair, creating a flickering cascade of textures: concrete, asphalt, grooves, cracks, grates, manhole covers, endless fossilized chewing gum, that yellow tactile paving, multi-colored pride crosswalks…

Davenport’s “politicization”—which his mom, in a startlingly frank exchange, makes a sincere effort to understand—brings him to a statue of P.T. Barnum recently erected in his hometown of Bethel, Connecticut, where he continues his disquisition on the legacy of the freak show, a tradition that he feels has not so much disappeared as transformed into something far more insidious. I Didn’t See You There is strongly thesis-driven, but also works fantastically as a compendium of relatable quotidian moments, like a carelessly discarded Lime scooter getting caught in the wheels of Davenport’s chair and him yelling, “Piece of shit!” Because that’s really what they are.