Scene Report is an irregular column in which Screen Slate contributors consider a recent cinematic event in retrospect.

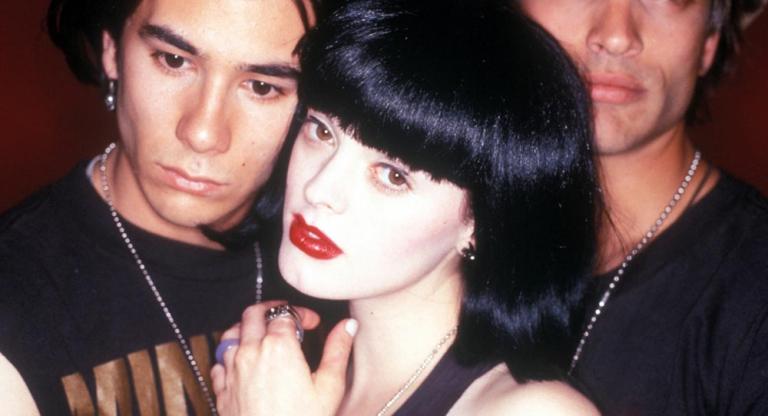

I arrived at Spectacle’s gialli marathon five minutes before noon. Giallo (so named for a series of Italian pulp novels with yellow covers) is a genre that tends to attract fervent enthusiasts. It’s a colorful amalgam of several B-movie genres, including sexploitation and crime drama, framed through the kaleidoscopic lens of Italian horror lore. Though not all gialli are Italian, they often play on decidedly Roman Catholic sensibilities, embracing gory topics with a tongue-in-cheek approach and melding Christian imagery with witchcraft. Despite the influx of recent boutique Blu-ray releases, even in New York it can be difficult to see any giallo other than a Dario Argento film on the big screen, which is why I naïvely jumped at the opportunity: a day-long, seven-film marathon, the title of each selection revealed only as it was about to screen.

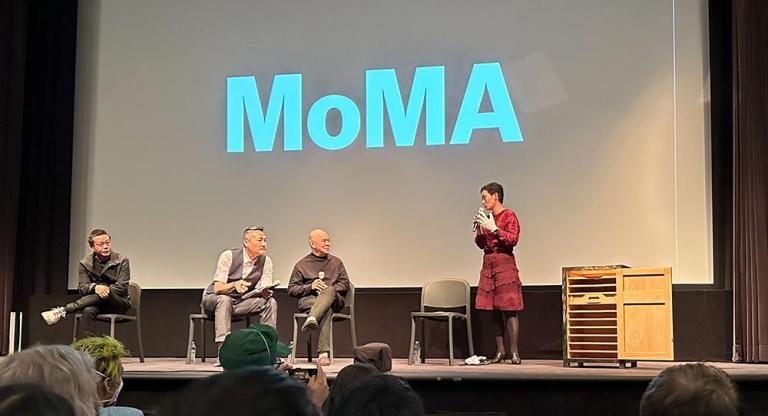

For those who didn’t have twelve hours to block out on a clear, temperate Saturday, Spectacle sold regular tickets for each film.The house was so packed that I settled onto the end of the bench that runs along the side of the narrow screening room, neck craned at the screen, notebook on my lap, feeling plucky, unaware of what the next twelve hours would do to me. Ben Harrison, the programmer, consecrated the day by announcing the first film: Oasis of Fear (Umberto Lenzi, 1971).

One of the opening lines, “Catholics love a little sin,” could be the tagline for giallo as a genre. The plot is characteristically thin (two young lovers/pornographers torture a repressed high-society MILF in her Italian mansion), but it captures what I adore about giallo as a whole: they always have time for an outfit change. About two-thirds of the way into Oasis, I witnessed a foot-long sandwich and tupperware of pasta salad emerge from someone’s backpack.

Going into the second film, Death Walks on High Heels (Luciano Ercoli, 1971), I get a needful second wind—perhaps because I’ve wrangled an actual seat. It’s a classic body swap, Vertigo-inspired film, the most well-known of the bunch. The protagonist is a cabaret performer who is horrible at her job. A guy behind me preemptively announces, “This scene is great.” People get up to use the bathroom like it’s going out of style.

Next up: Eye in the Labyrinth (Mario Caiano, 1972). Every text I send feels like a dispatch from the front lines. I am begging friends to bring me food and water, starting to understand why it’s called a marathon. Eye in the Labyrinth is about the horror of trying to solve a murder at a hippie commune where no one remembers what they did yesterday. It features the loudest slap sound effects I’ve ever heard and a slow-speed chase. It’s difficult to tell whether it earnestly embraces or critiques Freudian psychology: the protagonist murders her psychoanalyst after he stops sleeping with her, but she represses the memory.

It pairs nicely with the fourth film, My Dear Killer (Tonino Valerii, 1972), which is a classic police procedural with killer early-’70s interior design. Its opening shot is the most arresting of the day: a man is picked up and decapitated by a neon green crane. It also depicts the universal wish of womanhood: that one day, our trinkets will solve a murder investigation.

It is 8 p.m. My total caloric intake for the day has been a stale bagel and a Red Bull. I start to suspect that spectators are having food delivered to the theater. I cave and use the ten minutes between films to buy a $10 hummus wrap. The crowd has not thinned; in fact, a line has formed outside the door for the next feature. My companion is kicked to the back of the horde, and I worry I might get dishonorably discharged from Spectacle. There’s muttering about neon-yellow entry wristbands, as if we’re at a club, but my wrist is bare. Nevertheless, I persist.

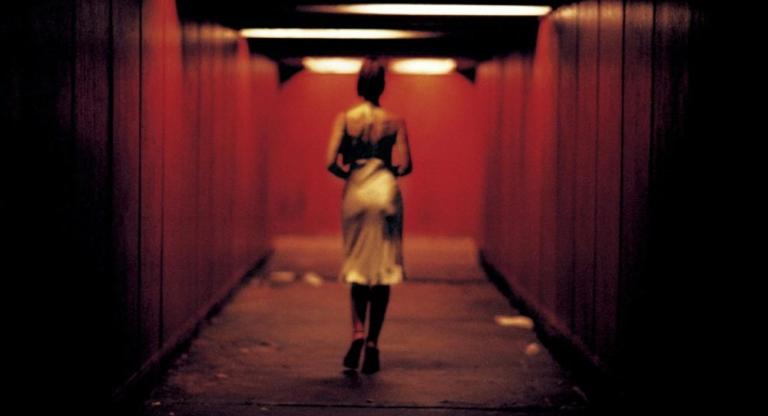

Footprints on the Moon (Luigi Bazzoni and Mario Fanelli, 1975), the fifth film of the day, is my favorite selection. It’s a surreal, ambitious, nonsensical addition to the genre, with brutalist sci-fi architecture and a baffling performance from Klaus Kinski. I’d describe Footprints as Last Year at Marienbad if the protagonist took tranquilizers and kept buying new wigs. The subtitler seems to be at war with the dialogue, which requires enough intellectual engagement to rouse me from the stupor of having sat in a dark room for eight hours.

Two films left and the madness hits. My companion threatens to leave and I, in my giallo-induced derangement, convince them to stay. I wash down Wegmans-brand Swedish Fish with lukewarm Coke Zero while a dead body hangs on screen. The penultimate film, What Have They Done to Your Daughters (Massimo Dallamano, 1974), tackles the bleak topic of high-power pedophile rings. Six movies in, we get our first majorly dismembered corpse and diegetic HIPAA violation.

It’s midnight. Our intrepid programmer introduces the last film: The Red-Stained Lawn (Riccardo Ghione, 1973). Its campy class analysis (rich libertines adopt and then murder unsuspecting vagabonds) re-energizes the still-packed audience. It demonstrates giallo’s peculiar ability to let hyperbole betray an actual truth. Stumbling out into the evening after twelve hours of shared psychosis, I text my friends that everyone should do this, whatever this is, at least once. That night, when my stiff neck hits the pillow, I dream in blood red and pulpy yellow.

"Seven Bloodstained Gialli: A Murder Mystery Marathon" screened at Spectacle on May 27.