Eastern Condors (1987) was an anomaly for Sammo Hung. Not only did the actor, director, and martial artist eschew the gut-busting slapstick that permeated his previous decade of action movies, he also altered his physique to match this shift in tone, trimming 30 pounds from a famously rotund frame. That isn’t to say that this pummeling, bullet-riddled misadventure is short on humor or outlandish choreography—a man is stabbed in the rectum within the first 15 minutes of the film—but here, the two are unwound from each other, with indiscriminate brutality rarely chastened by absurd comedy.

Set in 1976, Eastern Condors finds a group of immigrant convicts propelled into the jungles of Vietnam by the U.S. government, who failed to secure a cache of potentially devastating explosives when they withdrew from the region. The opening scene depicts a failed flag-raising by the military, establishing a tone of arch despondency while also complicating Hung’s appropriation of the ragtag men-on-a-mission template that Hollywood recycles to this day. The team is quickly assembled in montage, complete with visualized rap sheets and flurries of typewriter clicks; the men’s origins and crimes vary, but the lengths of their prison sentences, for the most part, do not. They are promised $200,000 if they survive the mission, but its details are gatekept by their tight-lipped, honor-bound head honcho Lieutenant Lam (Lam Ching-Ying).

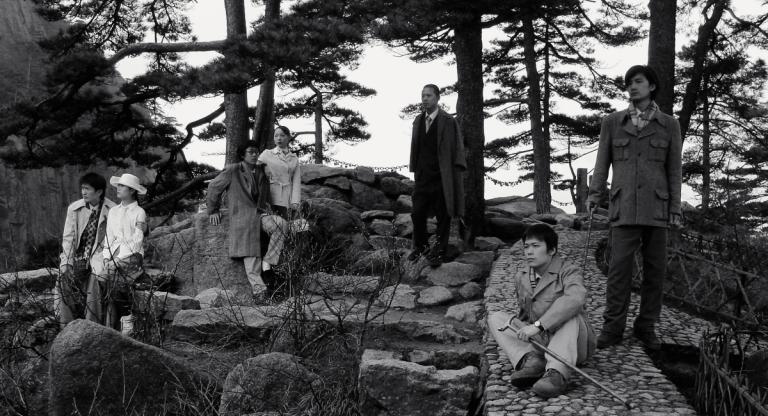

The group is cast out of an airplane, unaware of its destination, and left to parachute into enemy territory, where they rendezvous with a distaff trio of Cambodian guerilla fighters. Mayhem wastes no time descending upon this motley crew, and the strong are just as quickly separated from the weak; the two Viet-Chinese convicts (Sammo Hung & Corey Yuen, another legendary multi-hyphenate) conspire to protect their cohort along with the Lieutenant, the Cambodian commander (Joyce Godenzi), and a puckish expat on the hunt for gold (Yuen Biao). On the sidelines, the fraternity of two brothers is tested, an old man squares his reluctance to die for a pointless cause with a sense of duty to his makeshift brethren, and a spy infiltrates their ranks.

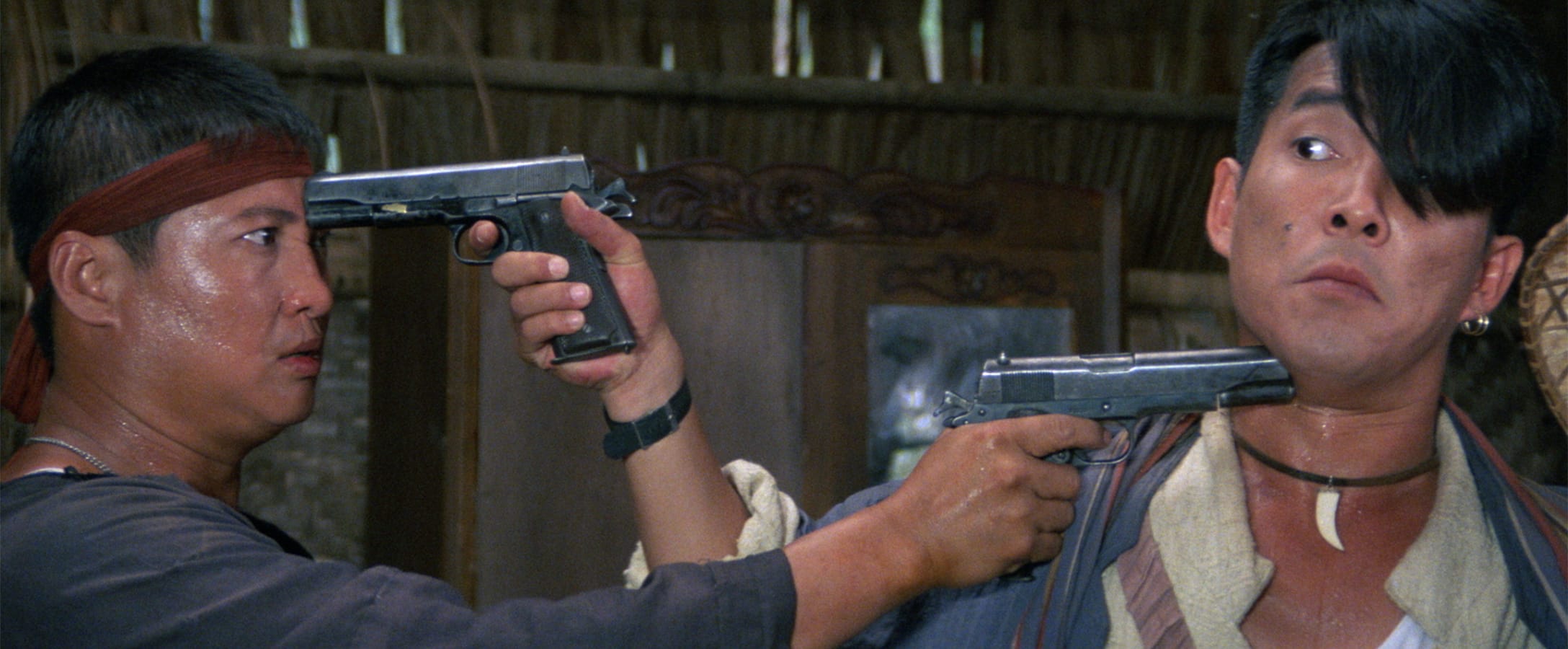

The film stages a series of increasingly violent showdowns with the Viet Cong, each filled with the kind of wincing bodily harm that has an audience wondering whether the actors really were beating each other to a pulp. Hung’s action staging shifts almost imperceptibly between giddy and sobering as the brute relish and machismo of Hollywood’s action tendencies collide with the collateral damage and bromantic bonds of Hong Kong’s “heroic bloodshed” tradition. A search-and-destroy sequence sees Hung kill multiple heavies by launching leaf-stems like arrows, and Biao bungeeing down from a tree vine as he swoops in for a melee brawl. A few scenes later, the gang is confined to the VC’s infamous water cages as two child soldiers take bets on a game of russian roulette on the dock above, using the prisoners as fodder. Our heroes’ inevitable jailbreak is undercut by a moment of mercy toward one of the children that guarantees the character’s demise.

Scores of faceless bad guys—with the exception of a giggly, fan-waving general—are eliminated as the Condors close in on the missile stores. Even though the Viet Cong poses a material threat to the lives of these characters—and as the Cambodians proffer, those of the surrounding regions—it is always clear where the blame for all of this violence lies. As the few surviving members of the crew take a well-earned breather, waiting for a rescue that may or may not come, one of them curses the imperial power that hung them out to dry, shouting “Go to Hell, America!” Hung’s character wonders: “You say that, but where have you decided to go?” “America, of course!”