Over the past year, we’ve become very familiar with the interiors of our own homes (those of us fortunate enough to have homes, anyway), but almost all other indoor spaces have become forbidden zones that suddenly exercise an unforeseen fascination. Confined to the city’s great outdoors, the mind reels with fantasies of what’s happening behind the closed doors of strangers’ homes. Walking down the street, the city’s walls feel even less porous, the buildings even more fortress-like. In the near-total absence of open public buildings, like libraries, the endless succession of private property appears even more callous and uncaring.

In the (hopefully) waning months of the pandemic, I’ll use this biweekly column to indulge my craving for the indoors by turning to that purveyor of vicarious experiences, the screen.

—

Anyone who’s surprised by how much money they’ve saved over the past 11 months will realize it’s because they’ve been doing most of their drinking at home. Unless you’re a Pacific Northwest libertarian or frequent the Staten Island watering hole that was declared an ‘autonomous zone’ where Cuomo’s oppressive COVID mandates don’t apply, you probably haven’t spent a lot of time rubbing shoulders with the regulars at the local dive. Now that every bar in the state has introduced menus of grapes and fish sticks, it’s easier to find a place that will let you drink indoors, but for the most part, bar culture is still stuck in pandemic purgatory right next to karaoke. For now, we have to settle for accessing this city’s bars indirectly, through cinema (and outdated Yelp reviews).

The improbably named writer-director-actor-lyricist James Bond III had a rising star moment in 1990 when his idiosyncratic coming-of-age vampire movie Def by Temptation was released. The New York Times’s Janet Maslin compared him to Spike Lee, while the Washington Post’s Richard Harrington drew parallels with Kathryn Bigelow. Variety praised the film for its “knowing humor, genuine tension, eroticism, and … terrific all-black cast” and Sight & Sound hailed it as a worthy successor to Bill Gunn’s equally undefinable Ganja & Hess. The Spike comparison was inescapable for Black independent directors at the time (just look at every review of Boyz N the Hood), and Def by Temptation, lensed by Lee cinematographer Ernest Dickerson and featuring Samuel L. Jackson and She’s Gotta Have It’s John Canada Terrell, fully warrants it. But that doesn’t account for the genuine enthusiasm the press of the day showed for this bizarre one-off. Def by Temptation probably deserves to be as legendary as Do the Right Thing, New Jack City, or Juice, but somehow history relegated it to the status of a campy curio.

This injustice can partly be explained by the film’s release by Troma Entertainment, whose output doesn’t typically get establishment recognition beyond bemused nods. A cornerstone of the Troma aesthetic is its bare-essentials budgeting, which translates to a reliance on location shooting. “The right location can give your movie a very high production value for little or no money,” Troma co-founder Lloyd Kaufman writes in Make Your Own Damn Movie! Secrets of a Renegade Director. “If some major studio wants to film a scene in a small-town bar, they’ll build the thing themselves and decorate it according to what they think a blue-collar dive bar should look like. … If an independent filmmaker wants a bar, he [sic] just needs to go find one.”

For Def by Temptation, the producers ventured to Fort Greene to find Two Steps Down, a bar and soul food joint that opened in 1969 and, as of this writing, appears to be closed. This is where a she-vampire simply called the Temptress (best-selling novelist Cynthia Bond) goes to re-up on victims, where Bill Nunn (Do the Right Thing, Money Train) tries to pick up women by telling them he’s a race car driver or a “kung fu surgeon,” and where a glass of Remy Martin (favored by one of the bar’s lone gay patrons) costs five dollars.

If I had a nickel for every time I’ve heard a place called a “neighborhood institution,” I’d have to hire movers to go to Coinstar, but Two Steps Down seems to have truly deserved this moniker. When Yvette Mayo first opened the space on Dekalb Avenue in 1969, there were hardly any other restaurants in the vicinity. Her daughters Renee and Rhonda eventually took over and some years ago were even discussing expansion, but recently the establishment seems to have gone dark. (A neighbor told me that the establishment has appeared to be completely closed during the pandemic, but undergoing some sort of renovation.) Let’s hope it doesn’t end up joining the hundreds of bars and restaurants that have been forced to close as a result of the New York state government dragging its feet on rent forgiveness.

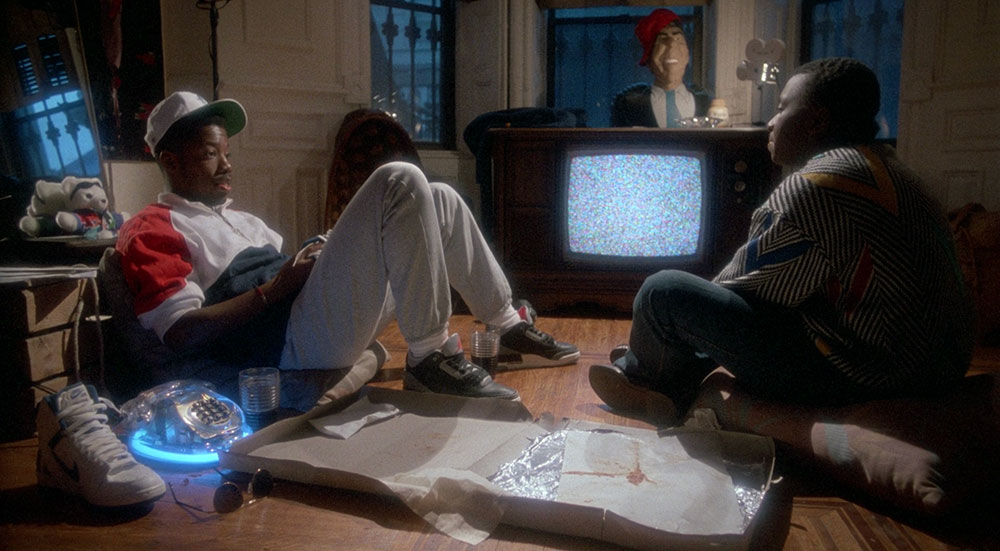

Two Steps Down is one of only two principal locations in Def by Temptation. The other is K’s (Kadeem Hardison) apartment where his little brother Joel (James Bond III himself) stays after arriving from the South. (Establishing shots of Joel’s house in “North Carolina” are actually of 200 Lafayette Avenue, a striking 1845 townhouse in Clinton Hill sided with bright yellow clapboards.) It’s in here that the film’s tone departs from the campy horror and comedic registers and settles on a surprisingly artless and intimate — almost observational — feel, as K and Joel have a series of heart-to-hearts about K’s movie career (with roles in Shakedown on Reed Avenue and Born in Bed-Stuy — I wish they were real!), Joel’s plans to become a minister, and the deprived and desperate “victims of economics and violent Reaganomics” who populate the big city. Having spent months mostly seeing my friends on their stoops in 15-minute intervals, the sight of these reunited brothers catching up cross-legged on cushions is almost too cozy to bear.

Sight & Sound’s Kim Newman saw Def by Temptation as a sign of the re-blossoming of independent Black cinema after the blaxploitation wave of Shaft, Superfly, and Blacula in the 70s. Aesthetically (location shooting, camp) and thematically (Jezebel trope, solidarity) Def fits squarely in that lineage and prefigures future developments in Black horror (for example, I’d have a hard time believing that the famous blood rave in 1998’s Blade wasn’t inspired by the Temptress’s blood shower) and maybe even in rap videos (Dickerson uses a fisheye lens almost as liberally as Hype Williams). But Def also owes a clear debt to Videodrome (1983), directly lifting the elastically reaching TV screen motif from the Canadian perennial. There’s maybe even a hint of Cassavetes’s maundering yet highly deliberate brand of dialogue. These echoes make this understated tale of satanic lust and rural/urban culture shock a generic headscratcher and stylistically more ambiguous than its association with Troma might suggest. (The film has since been rereleased on disc by Vinegar Syndrome, where it sits along other arthouse/genre hybrids by Black filmmakers, such as the works of Jamaa Fanaka.)

Until a few more hundred thousand New Yorkers get their vaccines, I’m going to stay out of this city’s surviving bars and enjoy them from the safe distance of the silver screen. Want to go to the 21 Club on 52nd Street? You can’t — it closed in December. But you can watch Michael Douglas teach Charlie Sheen how to insider trade there in Wall Street (1987). Or you can watch glib Burt Lancaster verbally skewer Tony Curtis there in The Sweet Smell of Success (1957). Want to go to P.J. Clarke’s on Third Avenue? You can’t — yet. It’s temporarily closed. But you can watch Ray Milland warding off delirium tremens there in The Lost Weekend (1945).

This is what we’ve come to, jealous of a frail man dying of alcoholism and resented by his family. But soon we’ll all be back in the bar together, sliding beers down the counter and breaking chairs over each other’s heads. Or whatever we used to do in them — I honestly can’t remember.