Anthology Film Archives is honoring the ubiquitous character actor Udo Kier with a series that represents a small fraction of his colossal filmography of over two hundred films. For example, the series somewhat disappointingly omits Ace Ventura: Pet Detective (1994), which paired Kier with one of the only American actors who can match his intensity. Instead, it features largely under-seen titles, mostly from Kier’s early and mid-career.

One such film is Werner Schroeter’s high-camp melodrama Flocons d’Or (1976), co-starring Bulle Ogier and Schroeter’s muse Magdalena Montezuma. Kier disappears after minute five and doesn’t return to the screen until two hours later, creating—at least in the context of this retrospective—a sense of anticipation that pays off majestically when he reappears to steal the scene with his angelic looks and highly physical acting style. Kier’s early performances are imbued with an almost disconcerting agility, a sinewy tension that quivers just behind his mountain-spring-blue eyes; in his first feature, Mark of the Devil (1970)—also included in Anthology’s series—he commands the screen with an astonishing economy of means, largely through his piercing gaze. In Flocons he is already in his thirties, and while his boyish looks remain, his performance has become more complex, harboring a wellspring of longing and regret that was absent in the skin-deep, Warholian mask of his earliest roles.

This is the contradiction that has characterized the evolution of Kier’s persona from eye candy to disturbing eminence: a handsome and sensitive actor capable of remarkable emotional subtlety, yet often typecast—especially later in his career—as a vaguely foreign scientist (Armageddon, End of Days), vampire (Blade), mysterious puppet master (Johnny Mnemonic), or human avatar of Satan (The Kingdom). Whence this dualism? Why the twin poles of pretty boy vs. evil incarnate, cherub vs. nightmare? Surveying his long career it’s hard to escape the conclusion that the main determinant over which of these opposing valences is harnessed depends on whether or not the director is gay. In Fassbinder and Schroeter’s work, Kier is all lips and eyelashes, tight jeans and low necklines. Michael Bay and Lars von Trier, by contrast, channel whatever is in him that is cold and ghoulish. Throughout Kier’s career, his queerness has been only periodically embraced; aside from Fassbinder and Schroeter, Gus Van Sant cast Kier in My Own Private Idaho as the well-dressed Hans who cruises for rough trade and performs an impromptu cabaret act, and Todd Stephens cast him in Swan Song (2018) as a geriatric queen back for one final turn in the spotlight.

Kier’s character in Flocons may not be explicitly queer, but Schroeter’s film is the gayest and campiest in the bunch. The film is carried almost entirely by Magdalena Montezuma, a prima donna of the highest caliber who appears in a series of fabulous outfits from a backless evening gown to a modern lamé suit, her hair alternately styled into a beehive or adorned with lilies. When she isn’t lip-syncing to an opera rendition of the “Marseillaise” she’s swooning from the shock of some revealed infidelity or stumbling smeary-mascaraed in heels across a field of rubble. The whole thing is a series of ambiguous tableaux unfettered by narrative coherence and imbued with an almost trollish durationalism: Ogier’s androgynous frame twirling in an industrial desert, Montezuma dancing to Miriam Makeba’s remarkably queer ballad “Forbidden Games,” Kier building a clumsily allegorical house of cards that keeps collapsing. There are visual evocations of Murnau and Kirchner and thematic evocations of Sunset Boulevard (1950), garish colors accentuating a longing for something irretrievably lost.

A 1981 interview between Schroeter and Michel Foucault—notable for the impassioned mutual admiration it reveals between these gay icons—sheds light on Schroeter’s unconventional approach to character-building:

Foucault: [Y]our way of completely avoiding the psychological film seems fruitful to me. Instead, we see bodies, faces, lips and eyes. You let them perform a kind of evidence of passion.

Schroeter: Psychology doesn’t interest me. I don’t believe in it.

This refusal to slot characters into legible psychological profiles is why Kier, a supremely physical, Meyerholdian actor, is a perfect match for Schroeter, for whom Montezuma’s mask-like face is also an ideal tool. Roland Barthes describes Greta Garbo as belonging to a “moment in cinema when the apprehension of the human countenance plunged crowds into the greatest perturbation.” Montezuma’s face, with its monumental proportions and disquieting expressiveness, also has this power.

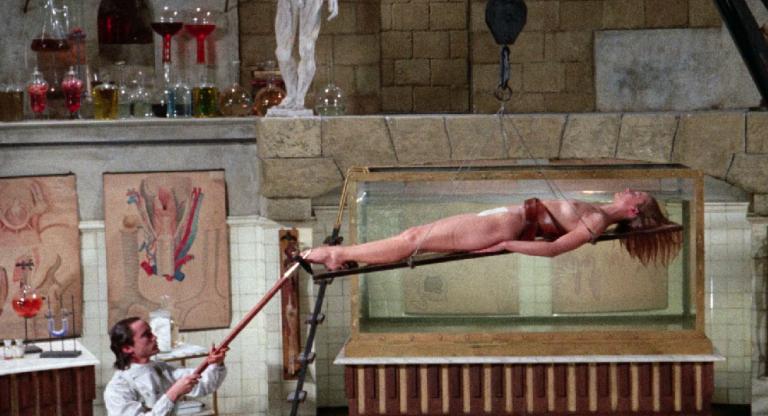

Flocons being screened at Anthology feels like something of a homecoming due to the many connections between the New York experimental and German queer film scenes. Schroeter was inspired to become a filmmaker at a screening of Twice a Man (1963) by Gregory J. Markopoulos, who co-founded the New American Cinema Group with Jonas Mekas and Andy Warhol, among others. Warhol and Paul Morrissey would go on to cast Kier in his first American films, Flesh for Frankenstein (1973) and Blood for Dracula (1974), which appear in this retrospective. In 1971, Schroeter met trans icon Candy Darling—whom Morrissey and Warhol had recently cast in Flesh (1968)—and cast her in The Death of Maria Malibran the following year. It was also at the Markopoulos screening that Schroeter first met Rosa von Praunheim, among the most militant queer filmmakers of the New German Cinema. Both Praunheim and Markopoulos worked with Tally Brown and other Warhol superstars.

Schroeter has described himself as a naïve admirer of Wagner, Novalis, and Hölderlin, but it has been argued that his refusal to distinguish between high and low art, granting both the same legitimacy as vehicles for emotional resonance, marks a decisive break from the tradition of German Romanticism. Flocons d’Or can be read as both a melodrama and an anti-melodrama, simultaneously reveling in and lampooning a particularly Teutonic death-cult sensibility. Although the film is obsessed with death, decay, and destiny, it displays such a blatant disregard for dramatic pacing that we’re undeniably in the realm of parody. Flocons is clearly a critique, but an incomplete one, a case of a student rebelling against his teacher but unable to escape the clutches of tradition, like Kier’s character in Mark of the Devil who refuses to see the faults of his witchfinder mentor until it’s too late.

Flocons d’Or screens tomorrow night, May 16, and on May 28, at Anthology Film Archives in 35mm as part of their Udo Kier retrospective. The actor will be in attendance for select screenings this Friday and Saturday, May 19 and 20.