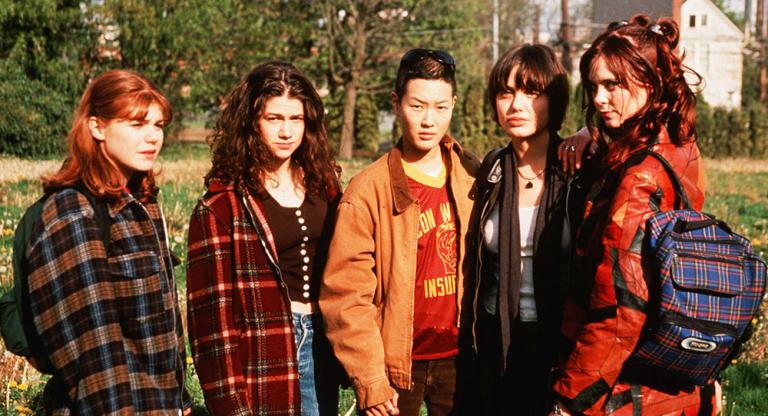

On an idyllic, sleepy island in the Pacific Northwest, five girls decide to leave society and take up residence in an abandoned house in the woods. They pack their bags and move in, delicately make the space their own, and develop a social contract for how they’ll navigate cohabitation and conflict. This is how Honeycomb (2022), the debut feature by Avalon Fast, begins. What follows is psychological drama, including betrayal and teenage savagery. It’s all fun and games until someone loses an eye.

Filmed on Cortes Island, off the coast of mainland British Columbia, Honeycomb drops the viewer into a bucolic setting and lets summer take its toll. The girls’ idyllic commune becomes sun-bleached, and by the end they’re raw and exposed. Avalon Fast, fresh out of high school at the time, recruited her friends to be cast and crew members, and the group made the trek to and from the island several times over the course of the summer. What resulted was a DIY movie that feels like a cult classic to be, a mix of coming-of-age drama and regional horror that is sure to inspire other young filmmakers. Honeycomb’s almost non-existent budget and unapologetically girlish energy conveys the femininity of Sofia Coppola with the riot grrrl sensibility of Sarah Jacobson. It’s a unique treat amidst today’s independent genre film landscape.

While Honeycomb premiered virtually at the Slamdance Film Festival in 2022, and had a Canadian premiere at the 2022 Fantasia Film Festival, it has yet to have a proper theatrical run. You can catch it this month at Spectacle Theater in a limited engagement.

I spoke with Avalon Fast, the director and queen bee herself, about capturing teenagehood on film, the pleasure of making a movie with your friends, and what comes next.

Stephanie Monohan: I wanted to start off by asking about the setting because some people may not be familiar with the islands of British Columbia where you shot the film. What was it like to grow up there?

Avalon Fast: Cortes Island is two ferry rides away from the island where I grew up. So it takes about four hours to make your way over there to Cortes through ferries and hitchhiking. Some of these kids that I grew up with lived on that island and would just stay at friends’ houses or rent spots so they could go to high school in the “big city,” which wasn’t a big city at all. Through becoming friends with those people, I started going over there in the summers, and the places we hung out, like the lake and the skatepark, are the same places you see in Honeycomb. After maybe the third summer of doing it, it got kind of mundane. I know all these people way too well, and we’ve done this thing too many times. It was so lovely when I was learning how to be a young teenager, and then it was so boring and annoying when I was ready to become an adult.

SM: So which came first: the concept you had for the movie, or the idea of “I want to make a movie with my friends to capture this time in our lives?” Or were they interconnected?

AF: I really wanted to make a feature, and I was on Cortes when I came up with the idea. It was the end of the summer. I had just graduated, and I was walking around the island a lot and reflecting. My original idea was that all these girls would take up residence in a big barn because there’s a spot on Cortes that is a giant field with a barn in the back distance. And I went to a party that night and I got everyone out on a mattress in the field, because that’s where we would all sleep and hang out when we would camp in our friend’s backyard. I just started explaining and kind of doing this pitch without really realizing, and a lot of my friends were like, “I would love to do that—we could all come back here next summer and do this again.” And that’s what ended up happening.

SM: So on an average day of shooting, how big was the crew?

AF: Probably ten, which was a lot of people. Because the primary cast was so large; there were five main girls that were generally in every shot. And then we’d have somebody on sound, somebody on the camera, and always someone different on the camera, which is the funniest thing. It was just whoever could figure it out. I would do a little crash course for them so they could shoot, and sometimes it was me.

SM: That is pretty next-level collaborative. Everyone there is wearing all these different hats and trading roles.

AF: Yeah, and it’s cute, too, because we get complimented on a scene or a piece of cinematography and different people can say, “Oh I shot that part.”

SM: At the end of the day, what would you say was the total budget?

AF: Because I took the summer off work, I like to wrap that up in the budget as well. So maybe $3,000. And then the actual [money] spent on the movie directly would have been under $1,000.

SM: The girls’ performances are pretty rigid at times, and their line delivery is very deliberate and stilted. It takes a bit of settling into, but once it clicks it’s really key to establishing the atmosphere among them. The boys speak very differently from one another. The way the girls talk is almost performative, which is actually pretty realistic, even if it's in an exaggerated way. Can you talk about how you directed the cast?

AF: Yeah, the kind of scripted, performative aspect was definitely purposeful. I find that the way women tend to speak is a lot more thoughtful [than men], and I wanted it to come across that they really were thinking hard about what they were saying and what they were doing. We did start to notice personalities coming through in the acting, especially with somebody like Destiny, who played Leader. She has that sassy, mean-girl thing going on really early in the film, and she asked if she could play that up since it was fun doing it. At the same time, I noticed there’s this sort of joint attitude among them where they all speak in this specific way. And I was really happy that came though because they seem really separate from the boys in that sense; there’s a really clear line.

SM: Could you talk more about the gender dynamics at play? Because it’s really fun to watch the power shift from the girls orienting themselves and their days around what the boys are doing to them having a lot of control over the role that the boys play in their lives. The boys get really frustrated with how the girls don’t even really seem to think about them anymore.

AF: That was a very real part of my friend group. A lot of these people I would hang out with on Cortes were older boys. I would go over to their houses with a couple of girlfriends, and we’d realize over the course of the evening that we’d spoken maybe ten words because it was such a boys’ conversation. And the boys had a band, and the boys were doing their shows, and we’d be quiet again just watching their show. That’s where Leader’s line comes from when she says, “I wish I could do something so I could perform.” Because I think that’s how we were feeling, like, Where is our chance to shine here in the group? It always felt like a bit of a boys’ club.

And I love all of my friends to death, but that was definitely a good way of saying to them, “This is how I feel sometimes.” Coming into ourselves as young adults, my girlfriends and I took some of that power back as we got more comfortable. We started leaving and having girls’ nights on purpose, which made the boys really sad, but we wanted space to talk. Honeycomb is basically them having an extended girls’ night in order to find their power.

SM: The drama between the girls is so well-drawn, even though it goes to this horrific place with the “suitable revenge,” where they collectively agree upon what to do when someone hurts another person. It’s so violent, but if you’ve ever been young and dealing with the heartbreak that can occur among girlfriends, it feels very emotionally true. How did you go about developing this tension and the unfolding of this drama?

AF: Learning how to communicate with my girlfriends and dealing with the ending of friendships when you’re young . . . I’ve experienced more pain having to do with that than with any romantic heartbreak in my life. I definitely drew from those experiences, where if somebody were to hurt me like that I would want to hurt them back the same way. And that’s the biggest rule they make. It’s interesting because women are known to be good at communication, but there’s also these weird rules we make that can make things sterile or not really leave room for more complicated feelings. The girls set up a means to purposefully avoid real, emotional pain, and then it ended up well . . . you know how it ended up.

SM: There’s a lot of media right now that is very interested in the darker relationships between teenage girls, but aside from your film, I struggle to think of any that’s been made by someone who is the age or recently the age of the characters they’re writing about. Do you still feel intimately connected to the person who just a couple years ago made this movie? Or do you feel like you’ve grown past that and maybe now feel nostalgic for that time?

AF: I feel like I wasn’t very self-aware while making this film. I think that I can almost understand what I was trying to do now that I’m older. I look back and I get all of these things that we’re talking about. At the time, I just wanted to make a movie with my friends, and it didn’t feel that deep. But now I’m realizing more and more that I accidentally made something that means a lot more than I thought it did. So I almost feel like I’m growing a stronger connection to Honeycomb all the time, and I really enjoy its presence in my life. Not only for the nostalgia, but because I like what it stands for and what it’s done for me.

SM: Who are some of the filmmakers that inspired you in making this?

AF: The Virgin Suicides [1999] was one of the movies I made all the girls sit down and watch before we shot the movie. I watched a movie when I was in middle school called The Kings of Summer [2013], where they do something kind of similar and had similar dynamics, but nobody ever connects that movie to mine. People usually bring up Picnic at Hanging Rock [2018] or Yellowjackets [2021–]. I can see the connection, but they aren’t things I saw before I made Honeycomb. Another movie I’m obsessed with stylistically is Mandy [2018].

SM: Another great Pacific Northwest film. Outside of movies, is there any other artistic inspiration you were drawing from?

AF: I read The Girls by Emma Cline, which is a take on the Manson cult but coming from the point of view of a young woman who was infatuated with another young woman in the cult instead of the leader. I read it and thought, “That is how it would be.” People make the scenario out to be that all these girls were drawn to this mysterious man, but I bet a lot of these girls probably came because there were a bunch of other interesting women there. It just made so much sense to me. I tried to make everyone read it before we shot.

And my friends’ music inspired me as well. Max (Graham) did the entire score for Honeycomb for me and he is the main member of the band that’s in the film as well. He composed or had something to do with every single piece of music that’s in Honeycomb, and I just think he’s a genius.

SM: What do you have on the horizon? Are you working on anything right now? And do you want to stay in the horror or genre film space?

AF: I’m two months out from shooting my next feature, called Camp. So now this has become my new everything and I’m very excited about it. The biggest difference between Camp and Honeycomb is there’s a whole emotional storyline to go along with it. There’s love, there's heartbreak, there’s tragedy. That’s something that I’ve wanted to do and it feels more right for me. Those are the kinds of stories that I like to watch. So I’m excited to bring in the indie, strange element of Honeycomb but to a really thoughtful story that comes from me as a young adult, versus me as a teenager. I don’t really have any expectations for myself for the future regarding genre but I’ve always had a connection to horror and I have a feeling that it could stick around.

Honeycomb screens tomorrow evening, July 14, at Spectacle and is available on Blu-ray from Gold Ninja Video