Larry Cohen's 1974 mutant-baby-serial-killer film It's Alive looks and feels like every other B-budget horror picture shot quickly and cheaply in the schoolyards, backyards, and spanish-styled bungalows of West Los Angeles. The opening, handheld shots that outline the lives of a seemingly normal, white, middle-class family with a new child on the way, lead us to expect the worst for them. And in the space of 90 minutes our expectations are almost gratified.

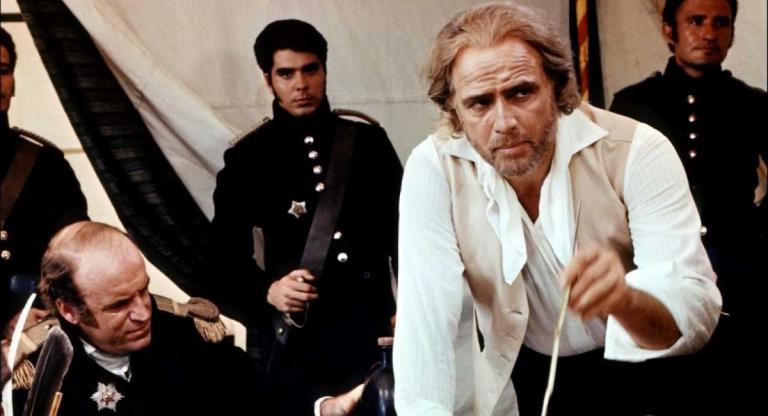

After the family, and the world, realize that the baby has been born a rampaging mutant, the bodies of doctors, policemen, a milkman, and a nameless musician on Santa Monica Boulevard rapidly pile up as the child crawls and kills across L.A.. The novelty of the plot quickly wears thin. But what's left is the utterly strange and transfixing image of the child's shattered father, played by the veteran character actor John P. Ryan. In scene after scene, Ryan contorts himself into the fractured image of the typical, white American male. We see the husband who feels trapped by the responsibilities of raising children and the unequivocal love of his wife. We see the citizen who trusts the law only as far as it will give him the gun and let him finish the job himself. And we see the individual whose identity is perverted: by the media, by shadowy corporations, and by his own, shallow ideals. And all of this is communicated through Ryan's eyes, his blank stare into the void of his wife's barren hospital room, and through his presence in space.

Because of Ryan's performance, It's Alive stands as more than a genre curiosity. Like its brilliant Bernard Herrmann score, there is something atonal about the film, which robs the pseudo-redemptive final scene of the catharsis that we usually expect from a horror movie ending. Instead, we are left with the lingering, solitary image of a man who does not understand himself—echoing the emptiness and absolute despair of another film that opened in 1974: Roman Polanski's Chinatown.