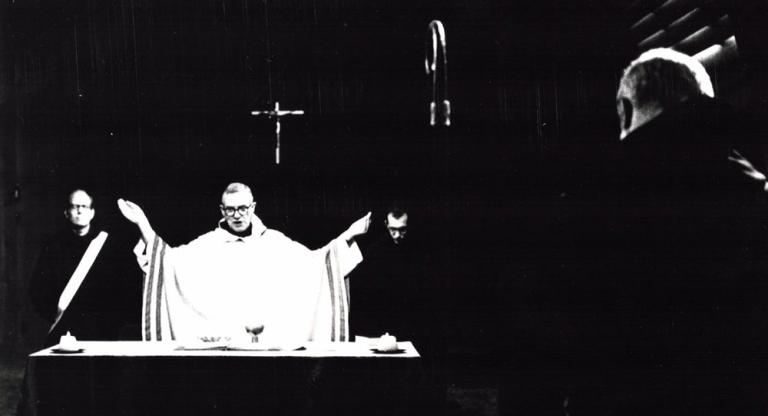

Mixing The Little Rascals, Jacques Tati, and Agatha Christie with Bressonian austerity, Bruno Dumont’s made-for-TV Li’l Quinquin juggles its myriad tones and reference points in a manner uniquely challenging yet immediately accessible. By counterposing a stilted dramatic styling and gruesome murder mystery with broad slapstick and adolescent game-playing, Li’l Quinquin is a perplexing commentary on the prejudices of modern life that juggles heavy overtones of the absurd and the existential. A funeral coming early in the film starts with despondent unease as the townsfolk appear lacking in concern yet turns towards an inappropriate sense of pathos during an out of place romantic pop song until the scene ultimately descends into farce when the priests start snickering and making faces during a moment of silence.

When a dead cow is discovered with the dismembered body of a local woman shoved up its backside, bumbling bushy-eyebrowed detective Van Der Weyden is on the scene with his stiff, robotic gait and constant facial spasms. While Van Der Weyden and his soft-spoken partner, Carpentier, drive around town hounding after clues, the corpse count multiples before they can even formulate a single suspect. Running circles around Van Der Weyden’s investigation is 10-year-old Quinquin and his band of prankster buddies. Bored by rural life, they spend their days throwing firecrackers at tourists, chasing down minorities, and inadvertently stumbling upon clues.

When the second victim turns out to be a muslim construction worker, Li’l Quinquin adds a stark portrait of racial and class tensions in northern France to its mix of pratfalls and gore. As Van Der Weyden berates a group of immigrants for not solely speaking French and a local girl hurls slurs at a dark skinned teen flirting with a white woman, the film juxtaposes the banal everyday violence of the townsfolk to the gruesome string of murders in a manner which would feel wholly tragic if it wasn’t for the cosmic stupidity of all involved.

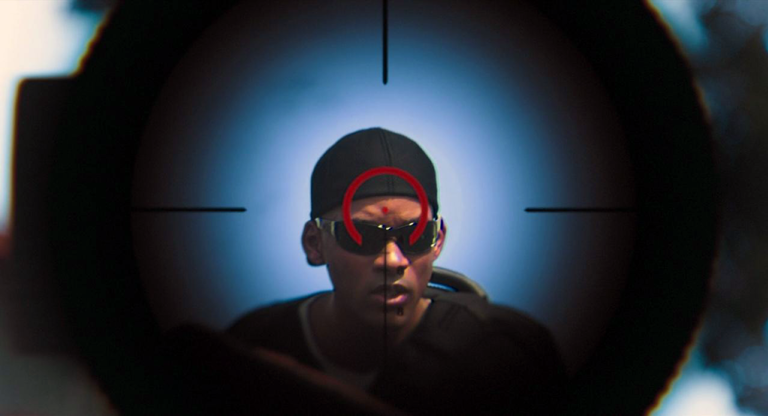

Playing as part of the same series at the Museum of the Moving Image is Bruno Dumont’s Li’l Quinquin sequel, Coincoin and The Extra Humans. This time Van Der Weyden, Carpentier, and a teenage Quinquin — here inexplicably called Coincoin — are pitted against a mysterious black goop which causes whomever it touches to flatulate out a soulless doppelganger. Ironically contrasting the townsfolk’s widespread fear of a nearby refugee camp and their bemused confusion in the face of this alien substance stripping them of their humanity, Dumont creates a world both more bitter in its grim portrayal of social prejudices and more farcical in its emphasis on slapstick and scatalogical humor.