The inimitable Agnès Varda graced New York City with her presence last week, in town for a special series organized by the French Institute Alliance Française (FIAF). Agnès Varda: Life as Art opened with a talk on February 28 to a blissfully sold-out crowd, followed by a string of sold-out appearances at FIAF and Film Society of Lincoln Center, and the opening of her first NYC solo gallery exhibition at Blum & Poe . As if the chance to hear her speak wasn’t enough, yet another gift: fans will be delighted to see Jacquot de Nantes , one of her most personal yet rarely screened works—an essential piece of the mellifluous, multifarious Agnès Varda puzzle.

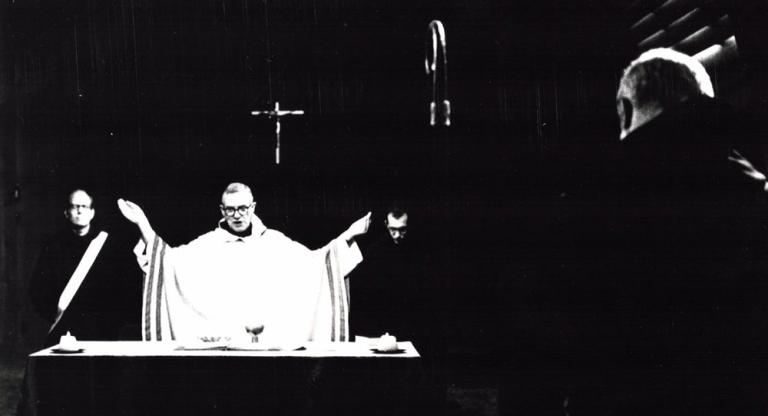

What began as a collaboration between Varda and her husband Jacques Demy ended as an elegy when Demy died in 1990, just before the film’s release. Despite its tragic (some may say sentimental—and let them, sentiment is not a dirty word) undertones, what’s wonderful about this film is the way in which it interweaves aspects of documentary, fiction, and biography to achieve a kind of circuitous clarity, a consonance and resonance of narrative and memory; of private experience and public expression; of affection and grief.

Jacquot de Nantes is quite unlike most biopics, considering its subject’s direct involvement in his own life’s dramatic re-enactment. What’s more, Demy’s life-threatening illness was well underway during production. And yet it is not so much his story that captivates (that of his childhood in war-torn Nantes) but hers. Varda’s devotion to depicting the details of, by, and for Demy—with all the love and tenderness of one who knows her subject inside and out—cuts deep. Alternating between reenacted childhood memories (themselves shifting between color and black-and-white), intercut with clips of Demy’s own films (future iterations of former memories) and documentary footage of Demy himself (mostly in macro, the most intimate of angles), Jacquot is perhaps the closest Varda comes to invoking that sacred feeling of saudade. The film closes rather abruptly with a brief, tuneful, and unaffected melody sung by Varda herself. For this moment alone, the film is worth seeing. Her singing voice (as with her artistic voice) is honest, direct, organic, and sublime. If there is a singular lesson to be learned from the film—and all of Varda’s artworks—it’s that the best we can do for ourselves and each other is to listen. No wonder why she loves the ocean so much.