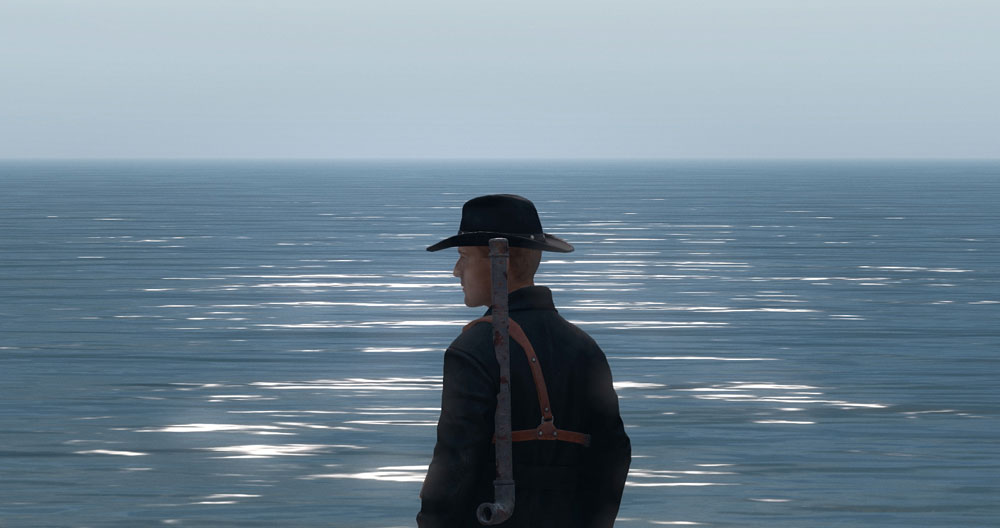

At this year’s Camden International Film Festival, among ambitious archival docs, intimate essay films, and talking-heads bonanzas on urgent political topics, one entry stood out like a glitch in the Matrix: Knit’s Island (2023), a feature shot entirely in an online multiplayer game by three French twenty-somethings: Ekiem Barbier, Guilhem Causse, and Quentin L'helgoualc’h. In DayZ, a game world situated in a fictional post-Soviet state after a zombie outbreak, players find food, weapons, and other survival implements while creating alliances and warring against other players. The filmmakers embedded themselves as a scrappy documentary crew with affable avatars, pledged not to arm themselves, and set out to comb the game’s 250-square-kilometer world for interview subjects. The result is a bafflingly lyrical study of loneliness and community, constraint and freedom. The cowboy avatar of a veteran Finnish player croons a thickly-accented rendition of a Waylon Jennings song, a South African player wearing a Punisher-skull gaiter waxes ontological about the reality of the game world, and a heavily armed German couple are heard over their headsets trying to wrangle their toddlers back into bed.

I contacted producer Boris Garavini who put me in touch with two of the directors, Ekiem and Guilhem, just as they were waiting to board a Marseille-bound flight at Montréal-Trudeau International Airport. The garbled transcript from our rushed interview has been translated from French and edited for clarity.

Cosmo Bjorkenheim: You’ve just shown Knit’s Island at CIFF and it met with a very positive response. What other audiences have seen this film so far?

Ekiem Barbier and Guilhem Causse: We’ve shown it to pretty much every kind of audience. We screened it for some high-school students. We took it to Visions du Réel [in Switzerland] and then we went to Romania and showed it at TIFF [Transylvania International Film Festival], a festival that programs fiction and documentaries. It was a much bigger audience; people came from the city to watch it.

CB: You spent almost a thousand hours in DayZ. How long of a process was it from conception to premiere?

EB & GC: We started by looking for video games we wanted to work on. We quickly landed on DayZ and did a lot of scouting over the course of weeks and months, finding the communities that interested us and gaining their trust. We followed these characters over a period of three or even four years. We were able to take all this time because we were working with a production company and had a little money, so we could afford to spread out all these work periods a little. Each stage was relatively long, whether it was development and writing, production, or post-production and editing, where we had sixteen weeks.

CB: Before Knit’s Island you made a film within Grand Theft Auto V called Marlowe Drive [2018].

EB & GC: That was at the École des Beaux-Arts. Toward the end of our studies, we formed this research group around video games, and we went into GTA V and produced this short film, a 35-minute film that we shot in six months. We made the music ourselves. So for Knit’s Island we reproduced the pattern—or at least the intention—of the short, but we really took our time so we could go much further and deeper in every aspect.

CB: Is there a chance that American audiences will see it?

EB & GC: The short was shown very little and it had a somewhat strange journey because it is a student film, so it was shown in schools, in media libraries, in art centers, places like that. There was no festival run, as it was completely self-produced. At this point, we might transform it in some way and put it on YouTube for free. That’s a possibility because we have full control over it and can do more or less what we want with it.

CB: Was your working method the same here as it was with Knit’s Island?

EB & GC: It was very different because in Marlowe Drive we only had one avatar and one camera. We'd invented a fictional character. In Knit’s Island we have three avatars and we're really playing ourselves: a cameraman, a technician, and an interlocutor. So there's this big difference in having created a team of three documentary filmmakers. The first one is more rudimentary, while in Knit’s Island we pushed every possible limit by making the experience more immersive for ourselves. It's really as if the three of us were teleported, totally immersed in the game.

CB: Are there other games you’re interested in exploring in the same way?

EB & GC: Of course, we'll be working on a series starting in a few days, in another video game created by the same developer [Bohemia Interactive] and ultra-modded by communities of players to make it more like a simulator of everyday life. And it's French servers, so it's other communities, other places, other issues. And so we're going to shoot there. I think there are plenty of other games that can do very different things with different subjects. It transports communities of people who can be very different. And all this changes the stakes of the filmed product.

What we're mainly interested in, at least for the moment, are games where you can embody an avatar and speak through this avatar who functions in a spatialized way, where there's an incarnation of the avatar that's really in a space. Right now we're trying to find things that are close to a form of reality that reminds us of our reality, so that we can make connections with it. It’s good to get a glimpse of what some of these embryos of the Metaverse might look like. Just to clarify though, this is totally the opposite of the capitalist Metaverse. These projects produce no money and it’s really something unique that belongs to the community. It’s not the same universe at all. Just to clarify.

CB: What surprised you the most during the filming of Knit’s Island? Were any of your expectations about the people you were going to interview not met? What were some surprising things that you learned about the participants?

EB & GC: Things that we expected and wanted to provoke a little—there’s the research that goes into the glitches and bugs of the game. We were really looking for these fault lines in the game and moments when the reality of the game itself collapses. As for the things we didn't expect at all—actually, we didn't expect anything, in the sense that it’s a milieu we knew very little about. But I'd say that what we didn't really expect was just how deep the links between the real and the virtual could go. Chill Pilgrim, a character in the film, tells us that he's played for twelve thousand hours and that, in the end, all he has left is the time he spent there. We personally hadn't anticipated that it would go this far for some people.

Something that really surprised us was when Covid came. Covid made our players realize just how much time they were spending in the game. The pandemic made it necessary to kill time through things like video games, which are the best way to spend an enormous amount of time very, very quickly. Instead of Covid allowing our players to play the game in a more liberated way, in a way that would make them feel less guilty and completely acceptable, it had the opposite effect. We lost a lot of characters who went off to do other things and who don't play anymore, who've realized that there's something else that's more important than this.

It created this paradox because they were already in the position of playing every day—sort of homebodies, interacting with others through the internet—and now, when they were finally allowed to do it, now that it was completely socially accepted as a way to spend one's entire life, they didn’t want to do it anymore.

Another surprise was how far people pushed the game’s realism, whether consciously or not. There were characters like Slugmite who claimed that she could recognize people without hearing them speak and from a distance, by their gestures. Not just by how they dressed and by the sound of their voice, but how they moved their avatar with their controller.

CB: Do you feel like you got to know the participants well even though you never met in real life?

EB & GC: We've cast a new eye on this world. People coming from a film or anthropology background may not be aware of this angle, and gamers won't necessarily either. We’ve developed a kind of intermediary reading by slipping ourselves into an avatar’s skin but remaining ourselves. It gave us access to a side of the players that they hadn't revealed to other people. Once we had asked them questions about how they view reality, what bridges there are between their real lives and the video game, etcetera, we had access to a whole new side of the gamers.

There were things we wanted to see but didn't think were possible, and they turned out to be real. Like how people can dance using their avatars. We wanted them to do it, we wanted to show it in the film, but we didn't even know if it was possible. It was.

CB: I can imagine a version of this film where Covid would have been a bigger theme. How did you decide how much to emphasize the pandemic and how much to de-emphasize it?

EB & GC: Covid was a complete surprise, and it really connected with our subject. It was crazy—everyone now had to live like gamers and be at home on their computers, communicating remotely. It was all so powerful and so obvious. But our film already had a subject, and it wasn't Covid. We didn't want to talk about it initially because we didn't know what it was. We didn't have enough perspective to make a film about it at the time, and at the same time it was so connected and interrelated that we couldn't dismiss it completely. So we left it as a kind of ghost wandering around the film without making it a subject.

It was kind of the same with the war in Ukraine. The war started when we were in the middle of editing. I was seeing all the images again, people with weapons, mercenaries, signs in Cyrillic, devastated towns. How could I not make the connection with a war in Ukraine that's going on right now? I thought to myself, we're cursed, we've got another thing coming.

CB: Some of the characters—like the Reverend—are looking in DayZ for some kind of tranquility, a place to meditate, and then there are some who treat the world of the game as a pure sadistic playground. But I don't think we meet any players who really approach it as a simulator for war or apocalypse. Did you encounter players who had an interest in survivalism or who were using the game as a way to prepare for something?

EB & GC: For a start, I don't think there were any people who were seriously thinking of training for survivalism in the game. But on the other hand there were plenty of people who enjoyed imagining it, like Rene, who you see at the beginning of the movie, who shows us the stars—he’s a big survivalist. With him we could really talk, really hang out over this question because he’s both a survivalist and an unconditional gaming enthusiast. There are actually maps of the game in his computer room and he has a YouTube channel in which he gives survival tips by implementing the game's functionalities: lighting fires, finding weapons, healing yourself, etcetera. But he also has things that are stronger, that are more or less poetic or that talk about social survival as well. Like he has a guide video on how to approach someone in the game. How do you behave? What do you say? Do you put your gun behind your back? How close do you get to someone in order to talk to them? What are the signs of a threat in someone you shouldn't approach? This guide on YouTube is quite unsettling because it's really a tutorial for some real eventuality in the future. The fact that he was making YouTube videos carried a certain reality.

CB: Do you feel that DayZ has any value as a simulator of a post-apocalyptic survival scenario?

EB & GC: I'd echo the players and say that as a team, yes, you learn things about how to help each other, when to act and when not, what feelings come over you, panic, all that. Here we are at the airport, so I'm thinking of flight simulators. If you learn in a flight simulator how to take off in a plane, there are lots of little things that you may have picked up on, but there's a whole feeling and mastery that you don't ultimately have. You need a real plane for that—or a real apocalypse. But ultimately a flight simulator is the inverse of DayZ; pilots really train on a flight simulator but it produces no emotion. By contrast, in DayZ you don't learn anything about how to light a fire with two pieces of wood, but emotionally you learn things. Simulations and games can also get you used to certain emotions, and then flatten them out a bit, make them more normal.

CB: We also have the U.S. military sponsoring the development of games like Call of Duty to prime players with a set of vocabularies and knowledge bases to prepare them for military service, to cultivate in them the thought patterns and language of warfare, right?

EB & GC: In the series we're working on now, there are people preparing for police school by using games where they play the police and detain and interrogate real people. It dematerializes the human relationship, and it's a lot easier to tase or arrest someone in a video game than it is to do it in real life. We're inclined to use violence on real bodies because we've trained to do it on virtual ones first. So yeah, I actually find it pretty scary that video games can be a vector for martial ideology.

There was something like that when I was younger, when I played a lot of Counter Strike. Even after having played for a long time, I didn't really have the impression that I had entered the symbolic space of killing people. It felt more like I was doing a performance of precision and movement that had nothing to do with killing anyone. I thought of it more like drawing with a mouse. That's what was so interesting in the end, and the weapons didn’t matter at all.

CB: Are there any interesting game developers you’re following?

EB & GC: There's Jonathan Blow, whom I like a lot, who has released, to name two, Braid and The Witness, which are puzzle games and incorporate the puzzle into the story itself. The puzzle is not disconnected from the game system and the story, so there's something very interesting there. Then there's Lucas Pope, who developed Papers, Please and Return of the Obra Dinn. Papers, Please is a game we've been talking about a lot, because it's a border-guard simulator that puts you in the shoes of a border guard and requires you to make difficult decisions. There's an ethical aspect to playing the game and making decisions in it. If you're wrong about who's crossing the border, you lose the game; to beat the game, you have to be ruthless and let nobody through. It’s a combination of gaming ethics and border-guard ethics, and it's very interesting. Then there's another [designer] that I really like, called Davey Wreden, who made The Beginner's Guide, and who, I think, was one of the first to really incorporate an embodied voice-over into a video game, and a kind of self-criticism, etcetera. These are three developers I follow closely.

CB: How about other filmmakers working within video game worlds whom you find interesting?

EB & GC: There really aren’t many directors who have worked the way we work. The documentary approach with the recreation of a virtual film crew, that hasn’t been done before. On the other hand, we've seen a lot of use of in-game images. Chris Marker is very important. He shot something in Second Life that is pretty unusual and invites us into a world, a server of his own that he's created in which there are some of his old creations. It’s a bizarre stroll through this world. He must have been 80 when he made this film. It’s his [final work], and it was shot in a video game, so he understood that something could happen in this place. After him, there’s Alain Della Negra, who is one of our main references. One of his films is called The Cat, the Reverend and the Slave [2009], which he made together with Kaori Kinoshita and which is also about people who play Second Life.

Not many filmmakers have the desire to insert themselves into video-game worlds, but there are some directors whose films we’ve seen over the last couple of years. Nicolas Bailleul, for example, whose film Les Survivants [2019] has an approach that resonates with us. He interviewed people in a battle royale game called PUBG: Battlegrounds in a way that's very similar to ours. And we feel a connection to [Werner] Herzog. If I may say so, Herzog tends to use reality as fiction in his documentaries. It was this approach that interested us. And I remember that even in one of his last films about the internet, he interviews young people who were addicted to video games, and you get the feeling that he can't really ask them any questions. And he says in voice-over that he regrets not having been able to ask them the right questions because he doesn't know anything, but you can sense that he’s attracted to it. I think if he was from the next generation, he would have done stuff like what we’re doing..

There aren't many people in France who work in this way. We’ve met them, we know them, we've seen their films. It’s something we did a lot of research on during the filmmaking process: to find out what had been done and what was being done. There's also a film by Total Refusal called Hardly Working [2022] that's entirely shot in Red Dead Redemption, but it's about bots, about NPCs. It’s different.

CB: I’ll let you go so you don’t miss your flight and get stranded in Québec.

EB & GC: Thank you!